High uncertainty doesn’t mean indefinite Fed inaction

Current macro and geopolitical uncertainty make high-confidence forecasting extremely difficult right now. Nevertheless, the case for multiple Fed rate cuts sooner rather than later remains compelling because:

- Inflation risks are manageable

- Labor market erosion is intensifying

- Policy is tight — and in some ways getting tighter, as the delayed impact of earlier tightening means some borrowing costs continue to rise even as the Fed cuts

The Fed should focus on the labor market, cut three times

The June summary of economic projections (SEP) maintained a median expectation of two Fed rate cuts this year. However, just a single “dot” now divides the two- versus one-cut scenarios, not to mention that seven of 19 FOMC members anticipate no cuts at all.

The new SEP shows higher inflation and lower growth — and a whole lot more uncertainty about which of these risks should be prioritized.

Despite tariffs and the evolving Middle East situation, we think the Federal Reserve (Fed) should pay more attention to the deteriorating labor market. Because policy works with such long lags, delaying the cuts at this stage would unnecessarily exacerbate recession risks.

We therefore retain our long-standing call for 75 basis points of cuts this year for the following three reasons.

Inflation risks are manageable

When the Fed last lowered interest rates in December 2024, headline PCE (personal consumption expenditure) inflation was 2.6% y/y and core PCE inflation was 2.9% y/y. By May 2025, the two measures had eased to 2.1% and 2.6% y/y, respectively. In other words, despite inflationary tariff developments, notable further inflation progress has been achieved in the interim.

Yes, inflation will rise in coming months as tariff effects eventually bleed into the data, but the uptick should be modest given offsetting disinflationary forces elsewhere, particularly in shelter, insurance, and discretionary services. With the marginal exception of two months in 2023, the FHFA data shows home price inflation now running at the lowest level since 2012. Various rent inflation metrics suggest some further moderation in this space. Hence, we project core PCE inflation at 2.8% y/y in Q4, below the latest SEP median forecast of 3.1% y/y.

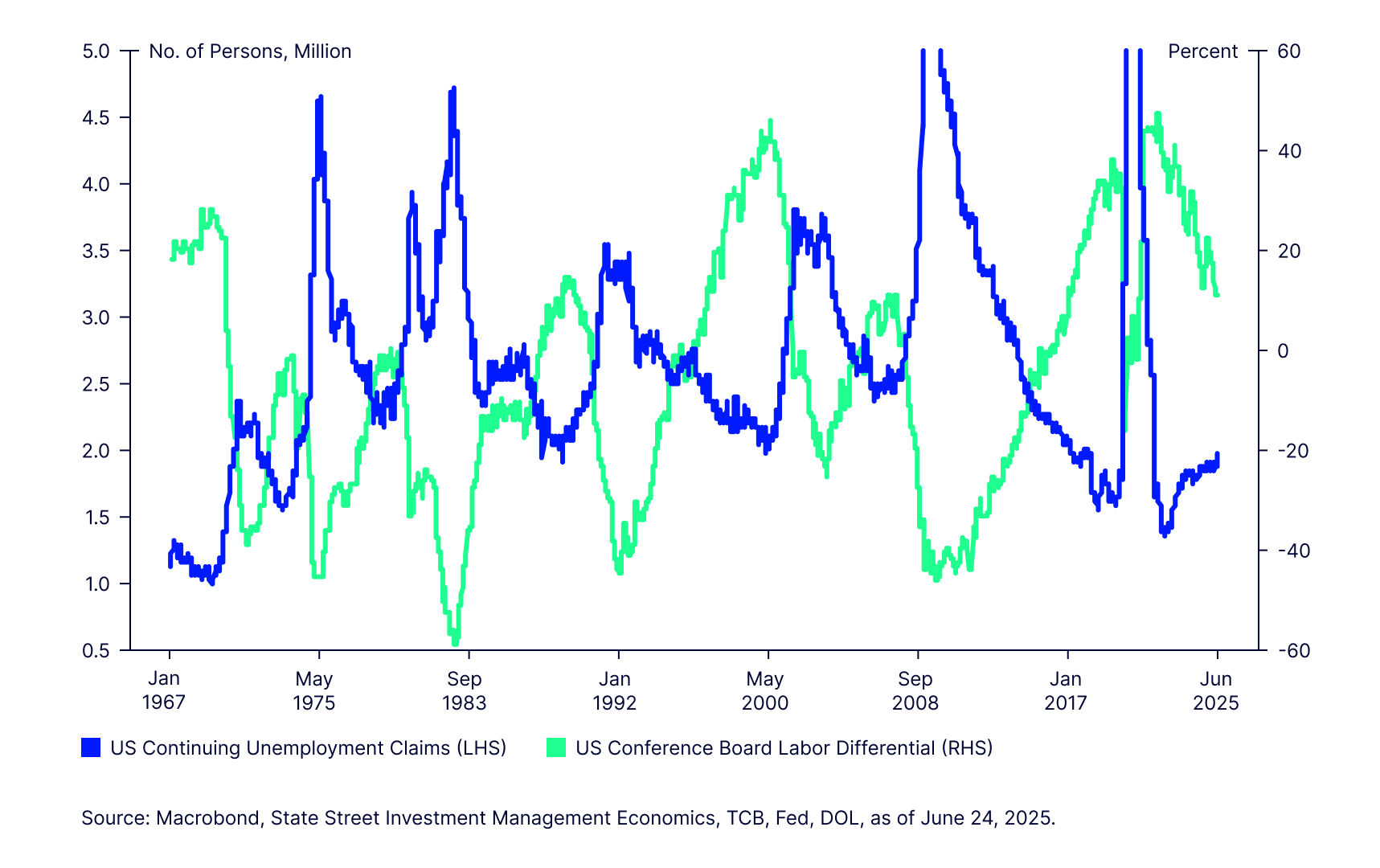

Figure 2: US labor market is loosening visibly

Labor market erosion is intensifying

The US unemployment rate has been remarkably stable over the past year, oscillating within an extremely narrow 0.2 percentage point range. It stood at 4.2% from March to May, precisely at the Fed’s presumed equilibrium or NAIRU level (non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment).

But with every other labor market indicator out there suggesting broadening erosion, it seems only a matter of time before the unemployment rate starts rising (Figures 2 and 3). In fact, had it not been for an unusually large decline in the labor force participation rate in May, we might have already seen an increase. Why? Because the pace of hiring is slowing and there is some evidence that layoffs are starting to broaden beyond the government sector, where DOGE actions triggered a severe spike in layoffs in February and March.

In the past four months, we’ve recorded three of the four highest private sector layoffs since 2012. It is incredibly important for the Fed to stem this increase if we are to preserve the soft landing and avoid a recession.

We feel strongly that some rate cuts now/soon would not make a difference to the inflation trajectory given inflationary pressures stem from tariffs, not from an accommodative monetary policy. But they could make a big difference in fending off a recession.

Policy is tight and in some ways getting tighter

The US economy withstood the Fed’s aggressive post-COVID tightening cycle impressively well, with real GDP growing 2.9% in 2023 and 2.8% in 2024. Surely, the policy stance must not be very restrictive if such performance was sustained? We disagree with that interpretation.

There were two main reasons why the economy did as well as it did despite Fed Funds in the 5.0% range, and both of those reasons no longer apply. First, there was an overabundance of liquidity thanks to generous fiscal transfers and the resulting excess savings cushion. Second, both households and corporations took advantage of extremely low interest rates in the early days of the pandemic to refinance debt. Therefore, the transmission of subsequent rate hikes was severely blunted.

But this slow transmission of monetary policy is now working in the opposite direction. For example, the effective mortgage rate on the stock of existing mortgages has now crossed above 4.0% and net interest expenses for non-financial corporations are steadily rising (Figure 4 and 5). Both will continue to worsen even as the Fed renews the cutting cycle. This is due not only to high rates on new borrowing but also due to refinancing of existing debt stock at higher rates.

We won’t even mention the federal government’s interest expenses, which are at record highs relative to revenues.

While it is true — as Governor Waller recently stated — that the Fed’s mandate is not to “provide cheap financing to the US government,” the mandate does ask that financing costs be set so as to promote full employment.

In our view, that is not currently the case. Rather, financing costs are too high, monetary policy is tight, and — due to the lagged effects noted above — getting tighter.

There are many ways to assess the degree of policy tightness. There is definite value in metrics such as financial conditions indexes, but they are better at capturing or identifying crises and financial market pressures as opposed to “real economy” stress.

Instead, we prefer comparing nominal GDP growth with prevailing interest rates as an indicator of “profit head room” and “incentive to invest.” This comparison (Figure 6) suggests borrowing conditions are tight to a degree that in the past 35 years has typically preceded recessions. The interpretation is very intuitive: to incentivize investment, there needs to be a delta between the cost of capital (proxied by Fed Funds) and the return on capital (proxied by nominal GDP growth). Some insurance cuts seem like a good idea given the current overlap between the two.

What could possibly go wrong?

We aren’t forecasting a recession, but we do worry about one.

Avoiding recession requires keeping the labor market from weakening materially. If it does, we could see a sharp deterioration in consumer delinquencies and the development of a negative feedback loop that leads to lower investment, more layoffs, etc.

The resumption of student loan data reporting by the credit bureaus has led to a spike in delinquencies recently, but the sharp deterioration in auto and credit card delinquencies has long preceded this. The level itself is troubling enough, but the fact that this is occurring while the unemployment rate is still at just 4.2% is highly concerning.

Consider that when the credit card delinquency rate was at similar levels in late 2009, the unemployment rate was about 10.0%. If the unemployment rate were to meaningfully deteriorate, there could be a further surge in delinquencies from today’s already-elevated level. Importantly, delinquencies may then seep into the mortgage space, which has so far been an area of consistent strength. We want it to stay that way, which is why the Fed should prioritize the health of the labor market.

We vote for a rate cut in July.