Democratizing Private Markets: Strategic Insights and the Path Forward

Once reserved for the world’s largest institutions, private markets are now at the forefront of investment innovation—offering unique opportunities, new risks, and unprecedented access for a broader range of investors. Discover how these markets are changing the rules of portfolio construction and what it means for the future of investing.

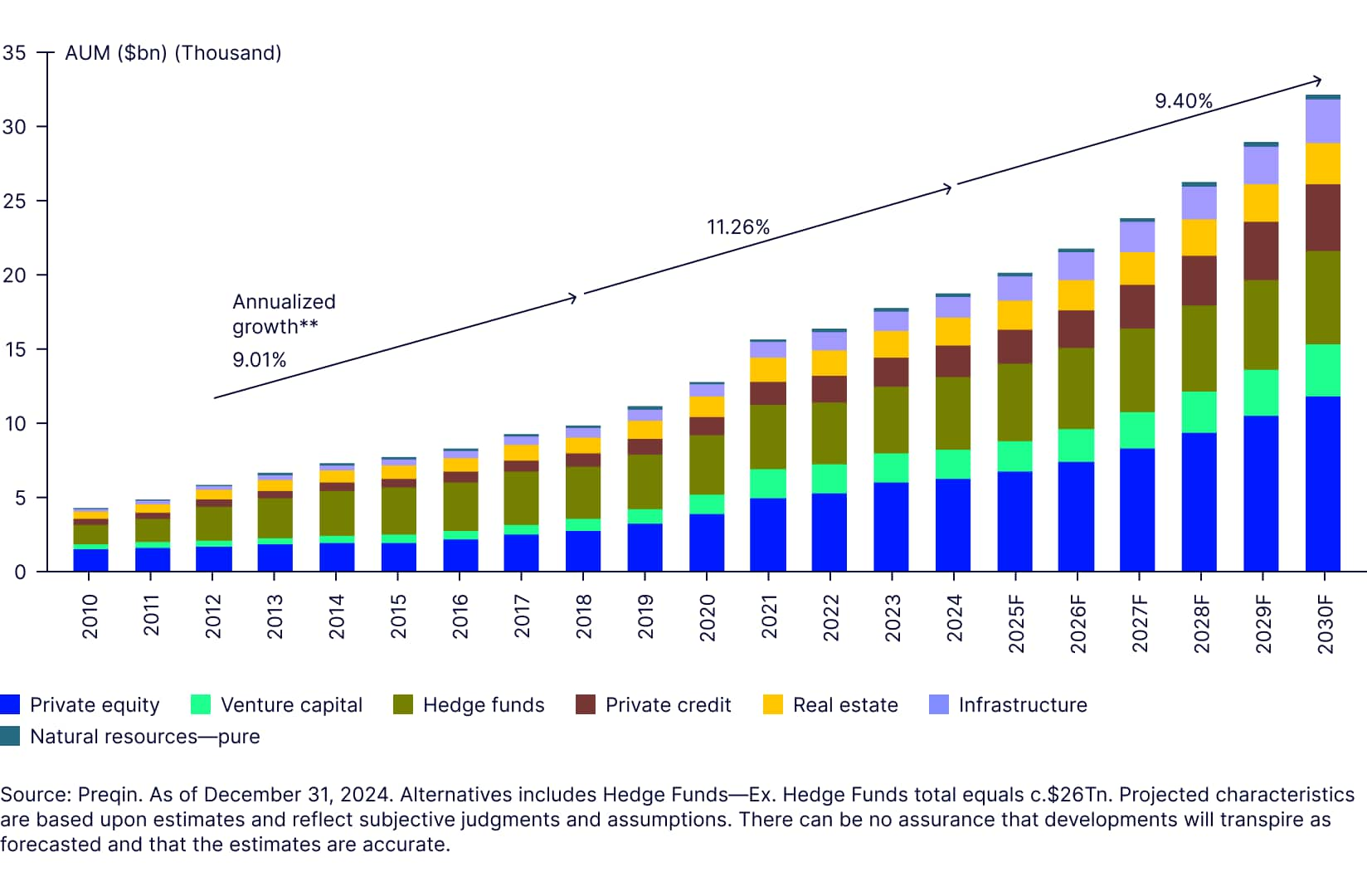

After the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, central banks around the globe lowered interest rates near zero, and kept them there for years, in hopes of supporting the weak economic recovery that ensued. Faced with a miniscule risk-free rate, the building block upon which all other asset class forecasts are based, investors were forced to seek out riskier growth assets to meet their financial obligations. It is during this time when private markets—and private equity especially—saw a meaningful uptick in assets under management (Figure 1). What was once a niche segment focused on idiosyncratic investment opportunities has evolved into a globally interconnected industry, to the point of eliciting systemic risk concerns.1 According to Prequin’s Private Markets in 2030 report, private markets are now projected to reach $26 trillion in assets under management (AUM) by 2030—or $30 trillion when including hedge funds—reflecting their growing role in institutional portfolios and the broader financial ecosystem.

Figure 1: Private Markets AUM growth by strategy – 2010-2030F

The appeal of private markets to a broad range of investors has been driven by two key factors:

(i) the potential for attractive excess returns, and

(ii) increasingly diverse opportunity sets compared to listed markets.

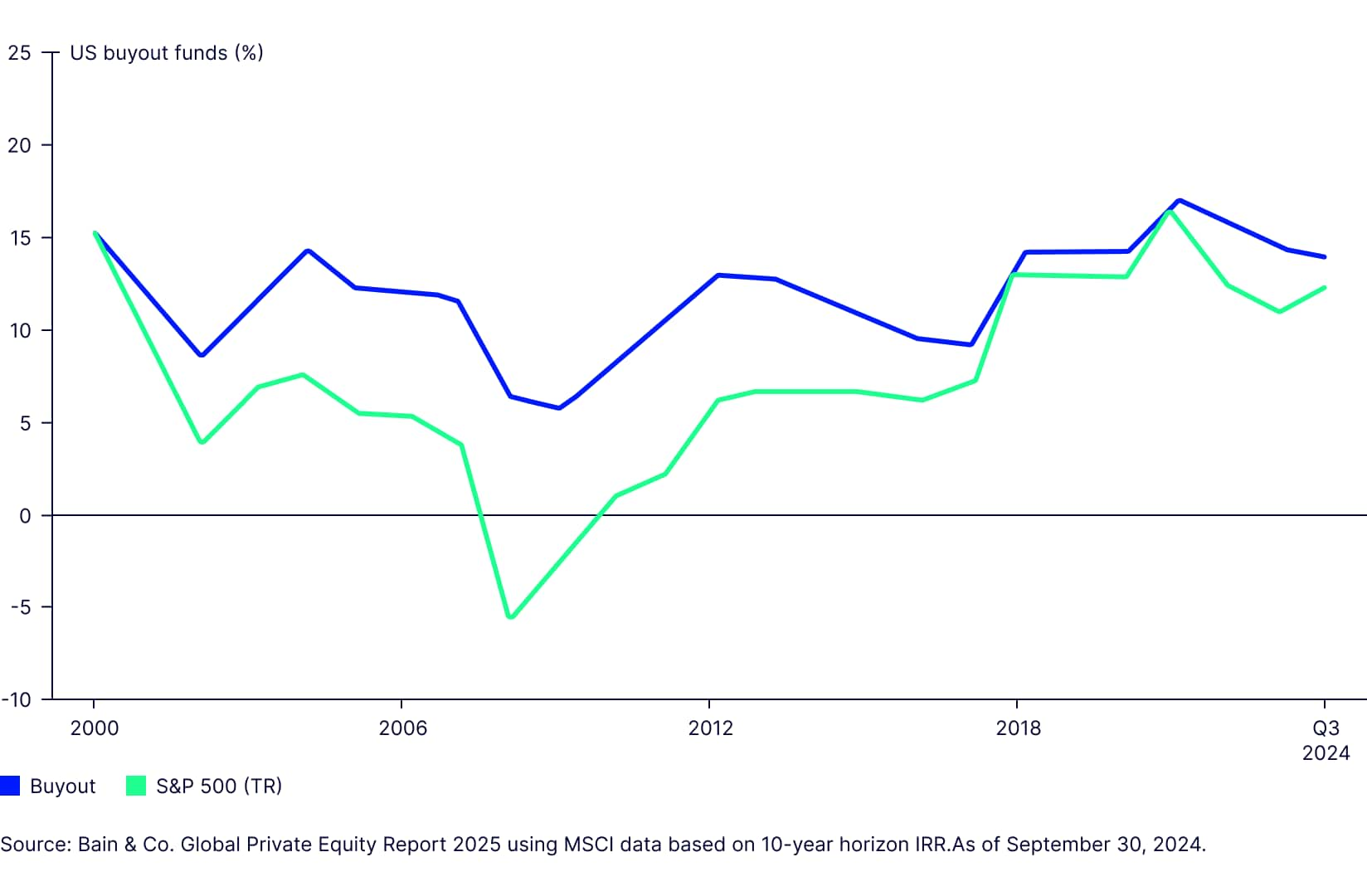

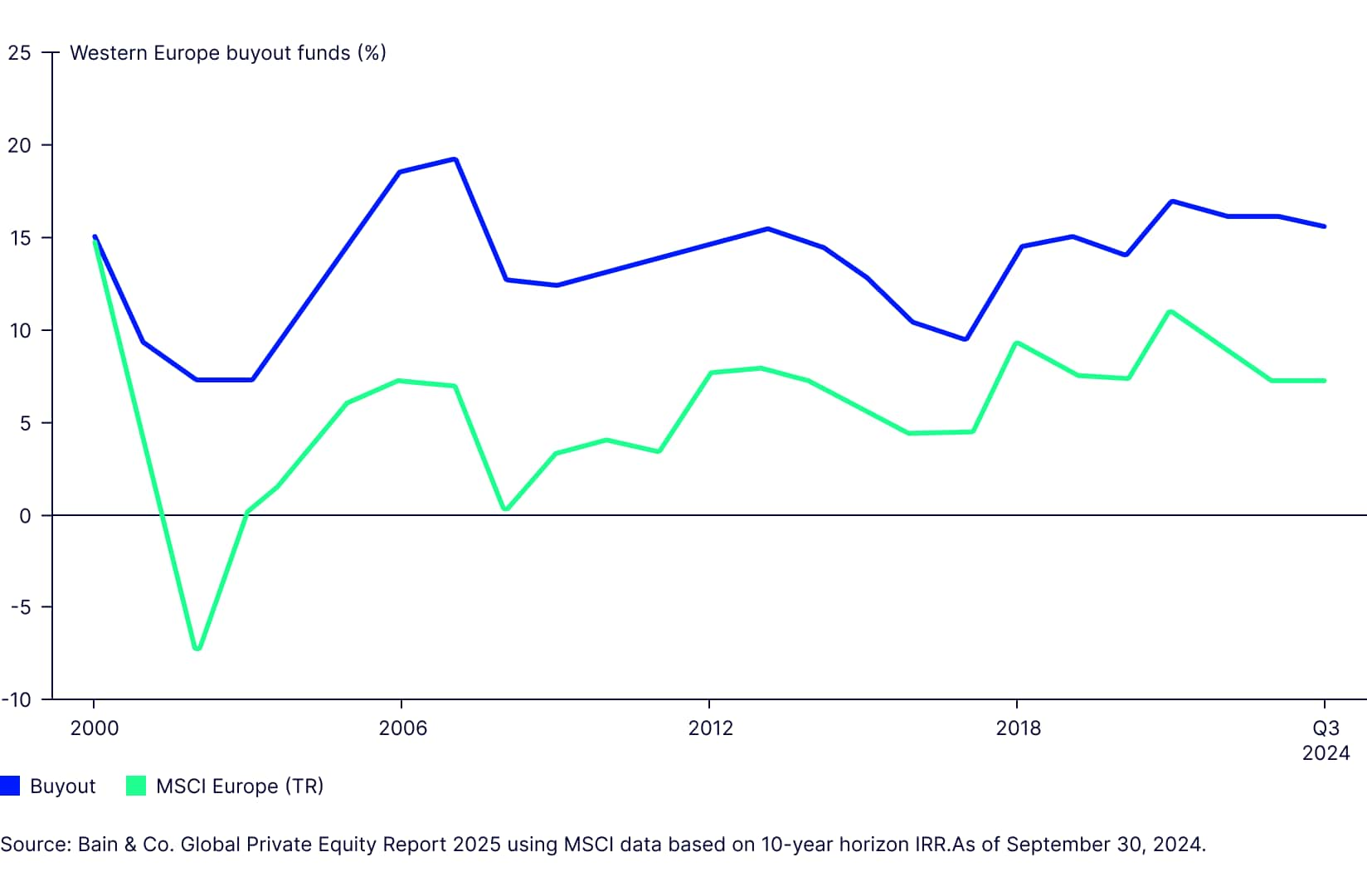

Figure 2: US and Europe private equity buyout performance versus public markets (2000-Q324)

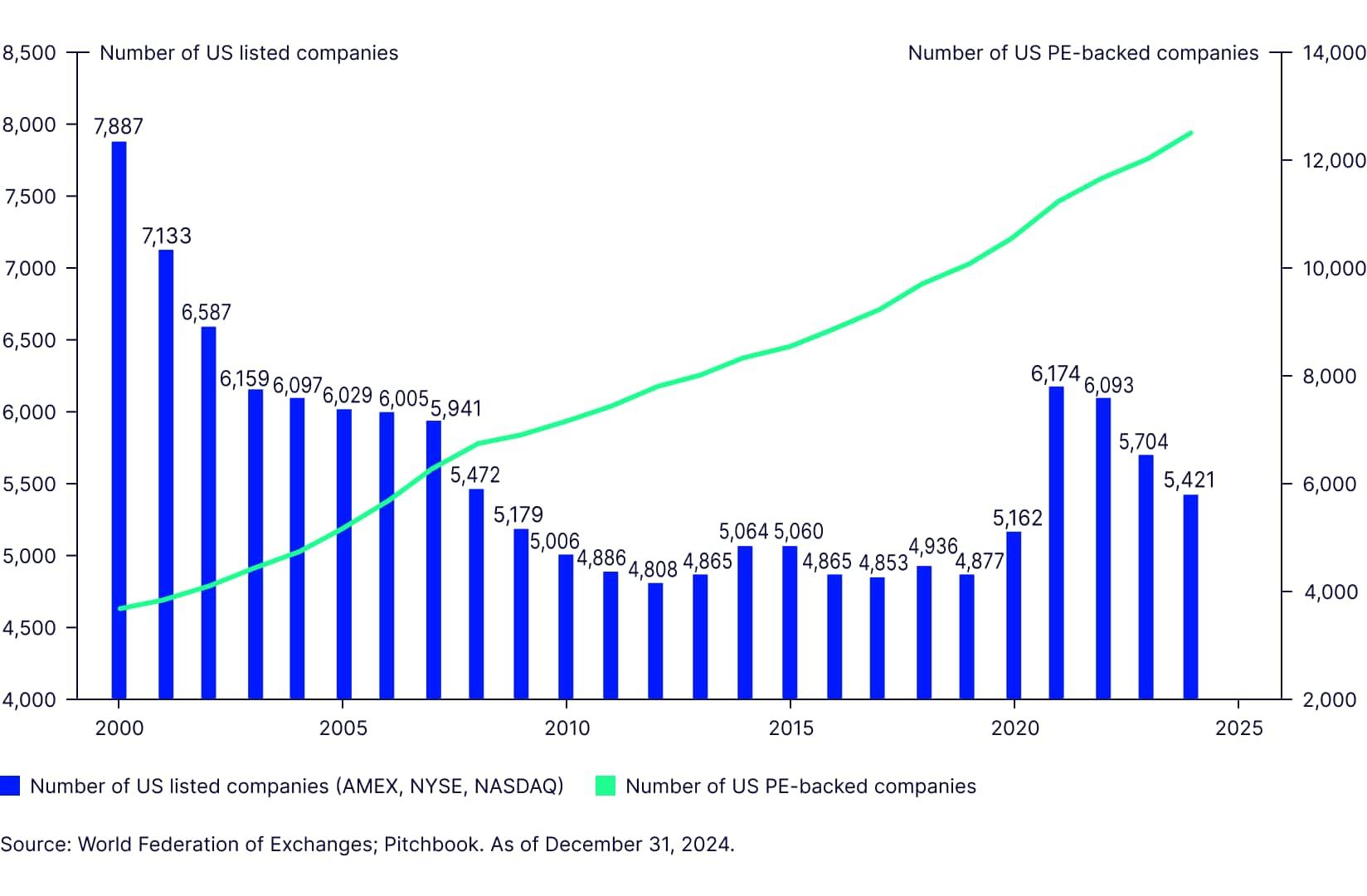

Private markets have consistently outperformed public markets over the long term—both in the US and Europe—although the performance gap in the US appears to be narrowing more recently (Figure 2). Several factors contribute to this outperformance, one of the most notable being the illiquidity premium: compensation for locking up capital over extended periods and allowing long-term investment theses to materialize. Even accepting that the increase in private capital bidding for target acquisitions may lead to lower prospective excess returns, an investor needs to consider how to incorporate private markets into an asset allocation framework. At a minimum, investors may want to expand their horizon to private markets to (re)gain access to the full investable universe. Since 2000, the number of companies listed on US exchanges has declined by over 30% (Figure 3), while those sponsored by US private equity firms has grown by more than 6x.

Figure 3: Number of US listed companies vs. US PE-backed companies

This decline in listed companies coincides with a rise in market concentration, with the market cap of the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 above 40% as of late 2025, far exceeding the previous high of 34% set in 1972 during the Nifty 50 era.2 Concomitantly, sector concentration within public market indices has increased, as Information Technology’s weight of 35.6% within the S&P 500 Index has surpassed the previous apex set during the 2000 Dot Com bubble.3 Private market allocations offer investors greater diversification, particularly at a time of heightened market concentration.

For liquid, easily tradeable assets, Mean-Variance Optimization using estimates of return, risk and correlation amongst investments in the opportunity set provides an intuitive, easy to use tool for establishing the required target weights for a desired portfolio return or risk level. Incorporating private markets into an asset allocation decision making framework brings unique challenges and nuances. How does one factor in the smoothness of returns from quarterly valuations and the subsequent impact on realized volatility numbers? At State Street Investment Management (SSIM), we developed a framework called Dual-Horizon Strategic Asset Allocation to address this conundrum.

Returns on most financial assets can be effectively separated into a long-term component linked to economic fundamentals and a short-term component linked to “excess volatility”4 or “noise.” The long-term component of returns are essentially the same for public equity and private equity (PE) in terms of direction and magnitude (after adjusting for leverage).

Public equity is exposed to excess volatility to a much higher degree, which explains the relative advantage that PE has in risk-adjusted returns during short- to medium-term horizons. This means, as the horizon extends, excess volatility gradually dissipates, resulting in the convergence of the price behavior between public equity and PE. The implication is that, for the requirements of strategic asset allocation (SAA), the horizon needs to be made appropriately long enough to accommodate for the persistent component of asset returns. Basing inputs on a long-horizon risk analysis harmonizes the risk-adjusted returns across asset classes, thereby removing the need to apply arbitrary adjustments to private asset risk figures prior to undertaking an optimization.

For a more in-depth discussion of this topic from State Street Investment Management’s Alexander Rudin and Daniel Farley, please refer to Dual-Horizon Strategic Asset Allocation | Portfolio Management Research.

Arriving at the desired private market target weights using an optimization framework is only half the battle. A common phrase in investing is “more art than science” and that is an apt description for the process required to transform a target weight into a real-world deployment of capital required to achieve that (moving) target.5 State Street Investment Management’s private markets team has over 30 years of history allocating on behalf of our Limited Partner clients and has developed a Path Forward model for private equity, private credit, and real estate as each asset class exhibits different characteristics. We use these models to size the amount of new commitments to deploy while keeping the allocation within a target range, taking into account uncalled capital commitments, the vintage of the existing funds, projected distributions and returns amongst other factors.

The Path Forward models were originally established to address the needs of large allocators making capital commitments over multiple years to funds entering the market gradually. Each commitment was expected to last anywhere from 7–10 years for a private credit fund, or 10-12 years (or more) for a private equity fund. These long lock-up periods, combined with drawdown structures and high minimum commitment thresholds—especially from the most sought-after General Partners—made it difficult for smaller institutions to participate, unless granted an exception at the GP’s discretion.

The first wave of democratized access to private markets came through fund-of-funds structures and feeder vehicles offered by private banks and wealth managers. These aggregated smaller commitments, enabling broader participation—albeit at the cost of multiple layers of fees for the end investor.

In recent years, however, the landscape has evolved significantly. The democratization of private markets has accelerated at an unprecedented pace, with individual investors expected to represent 22% of private markets AUM by 2030.6

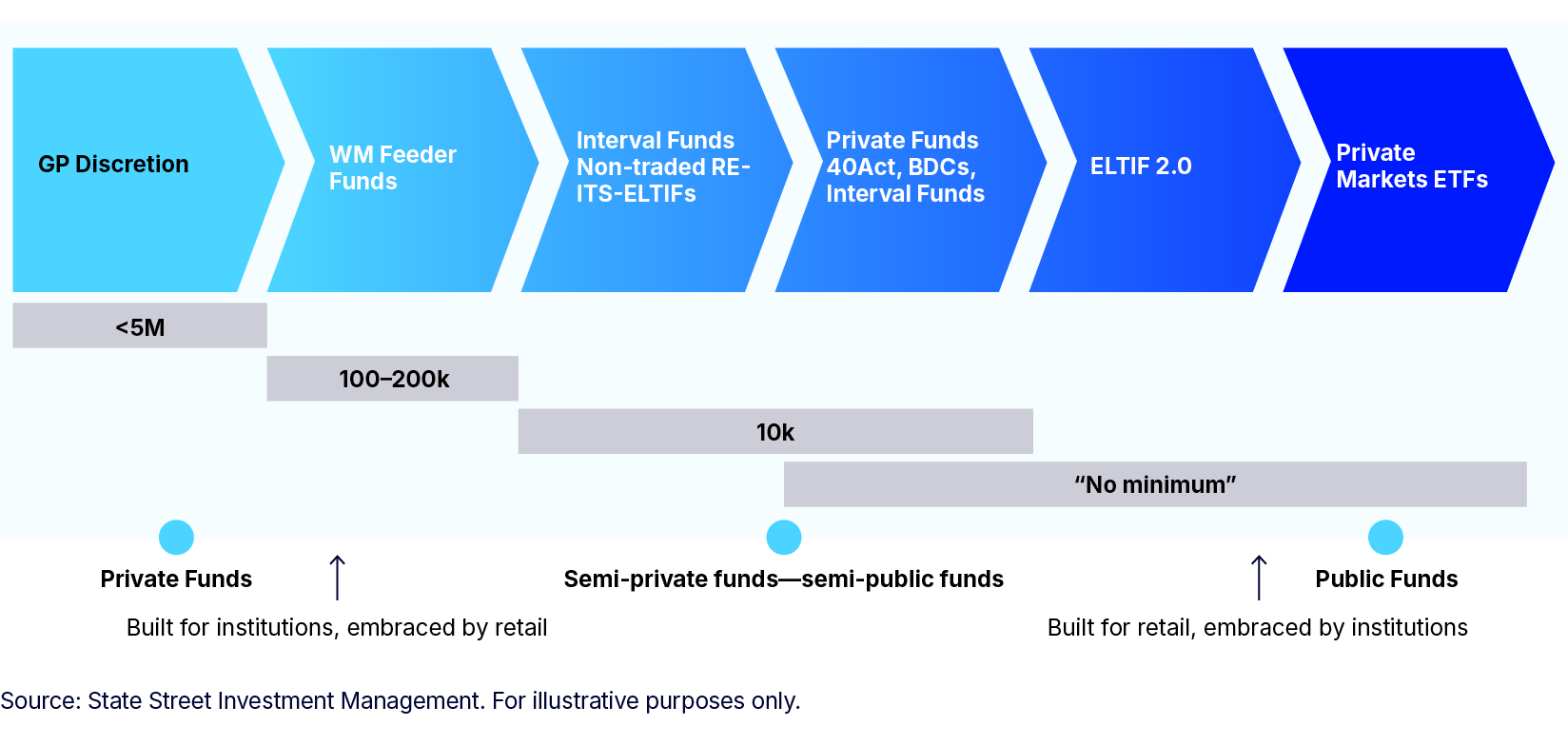

Figure 4: The evolution of private markets instruments from a democratization standpoint

Regulators have responded to this growing demand by enabling new structures and instruments. While individual access to private market funds was considered an exception a decade ago, a range of innovative solutions has emerged to expand reach. As illustrated in Figure 4, feeder funds now allow entry points as low as $100-200k, while newer vehicles—such as interval funds and tender offer funds in the US, and ELTIFs and LTAFs in Europe and the UK—offer intermittent liquidity and fully paid-in structures.

The most recent innovation, signaling a convergence between private and public markets, is the launch of the first-ever ETF embedding private market strategies (specifically private credit) by State Street Investment Management in 2025.7 While designed with individual retail investors in mind, these instruments can also serve institutional portfolios, thanks to their flexible liquidity profiles and diversified exposure—combining public and private market strategies in a single wrapper.

What we are witnessing in this democratization trend is a shift from products originally built for institutions and gradually adopted by retail investors, to solutions now being purpose-built for retail from the outset—yet with the potential to play a meaningful role in institutional portfolios as well.

Democratizing access to private markets

Over the last two decades, the weight of alternative assets, including private markets, in the global market portfolio has more than doubled from 6% to over 14%.8 Investors have increasingly turned to private market asset classes to enhance returns and diversify portfolio risk. Once the domain of only the largest and most sophisticated institutions, private markets are now accessible to a broader range of investors.

State Street Investment Management has over three decades of serving as a fiduciary for clients navigating the asset allocation and implementation decisions required for the successful integration, and ongoing management, of private market allocations in a total portfolio. Building on this foundation, State Street Investment Management is now at the forefront of the democratization trend—applying its expertise and rigor to expand access to this attractive asset class through highly innovative instruments and product solutions.