The Gulf Under Trump 2.0: Winner or Loser?

Improved US-GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) ties under President Trump could have positive long-term impacts on the region’s economic transformation. But will the volatility of America’s rapidly evolving macro policy pose risks to the region’s economy and capital markets in the short term?

Return of the Dealmaker

As in 2017, Trump’s first foreign visit was to the Gulf — Riyadh was his first stop. This act is not only symbolic, but underlines how well the Gulf is suited to Trump’s transactional approach to US foreign relations. Direct ties with Gulf states and overall amicable US foreign policy toward the region are likely to deliver material benefits in the long term. However, US policy volatility and resulting risks to global growth and higher US borrowing costs could generate negative spillover effects in the short term.

The GCC as a Winning Partner of the United States

The recent presidential visit to the Gulf led to formal agreements and public announcements of economic deals and future investments. As with many diplomatic events, some of the economic follow up will fail to materialize. But this focus hints at how much the Gulf may directly benefit in three key areas.

First, the US is facilitating access and partnership in the technologies of the future. Notably, Trump has upended the Biden policy of tiering access to US technology, where the Gulf countries had been placed in a middle tier, requiring case-by-case approval for export-controlled critical technology.

In its place, Trump has given a general green light and the Saudis unveiled their AI venture Humain, which will be able to purchase and deploy NVIDIA chips in its development. This is a major competitive advantage in the region’s efforts to develop home-grown AI companies.

Second, the US has committed to reforming the CFIUS process, which regulates foreign investment into national security-sensitive US sectors. This future reform will likely lower barriers for Gulf investors who had frequently been caught out and denied strategic investments. Together, these measures will likely facilitate closer links between the Gulf and US innovation and its corollary benefits.

Finally, the Gulf countries and the US appear now to have similar views on the broader strategic approach for the region. There are now growing efforts to build a stable security architecture that can facilitate unhindered growth in cross-regional commerce and trade. In this regard, the US policy pivot has already shown its potential to help with this. The US has delivered sanctions relief on Syria’s new regime; it has agreed to de-escalate tensions with the Houthi rebels in Yemen; it has launched serious talks on a renewed nuclear deal with Iran; and it has strived to bring lasting peace to the Gaza war.

If these efforts succeed, the path to making the Gulf an even greater economic corridor for Asia-Europe-US commerce are obvious. And in this context, the reduction of external problems means that Gulf countries can rely more on their own initiative to craft appealing business environments and solid regulatory frameworks that attract global capital and talent. For long-term growth, this is ultimately the most important differentiator.

Negative Spillover Effects From US Macro Policy Mix

The paradox here is that while US policy toward the Gulf has improved, its overall macro policy mix is deteriorating in ways that also have negative effects on the Gulf. US trade policy, especially, has been a source of global volatility. The GCC is not heavily exposed in a direct manner, given that only 3% of GCC exports go to the US, so the bilateral tariff increase is not a big headwind. Oman and Bahrain did enjoy free trade agreements with the US prior to “Liberation Day”, but some resolution on that front looks likely.

Rather, it is the global consequences of US policy uncertainty and Trump’s trade war that are having pernicious effects on the Gulf.

The former is lowering global growth prospects and, with it, global demand for oil. So, lower oil prices are likely in the coming year — our 2025 forecast range of $60-70 per barrel remains intact. This is below the fiscal breakeven price for most Gulf sovereigns and, thus, poses a challenge to fiscal support for economic transformation.

Worse, lower oil prices could be accompanied by higher borrowing costs due to US fiscal policy. The US yield curve continues to face further steepening, and continued fiscal largesse in the US could also limit the extent of Fed rate cuts. In either case, the weighted average yield of US debt is likely to rise (Figure 1) and, by extension, so are Gulf borrowing costs. The risk is firmly tilted one way — higher borrowing costs and lower oil revenues.

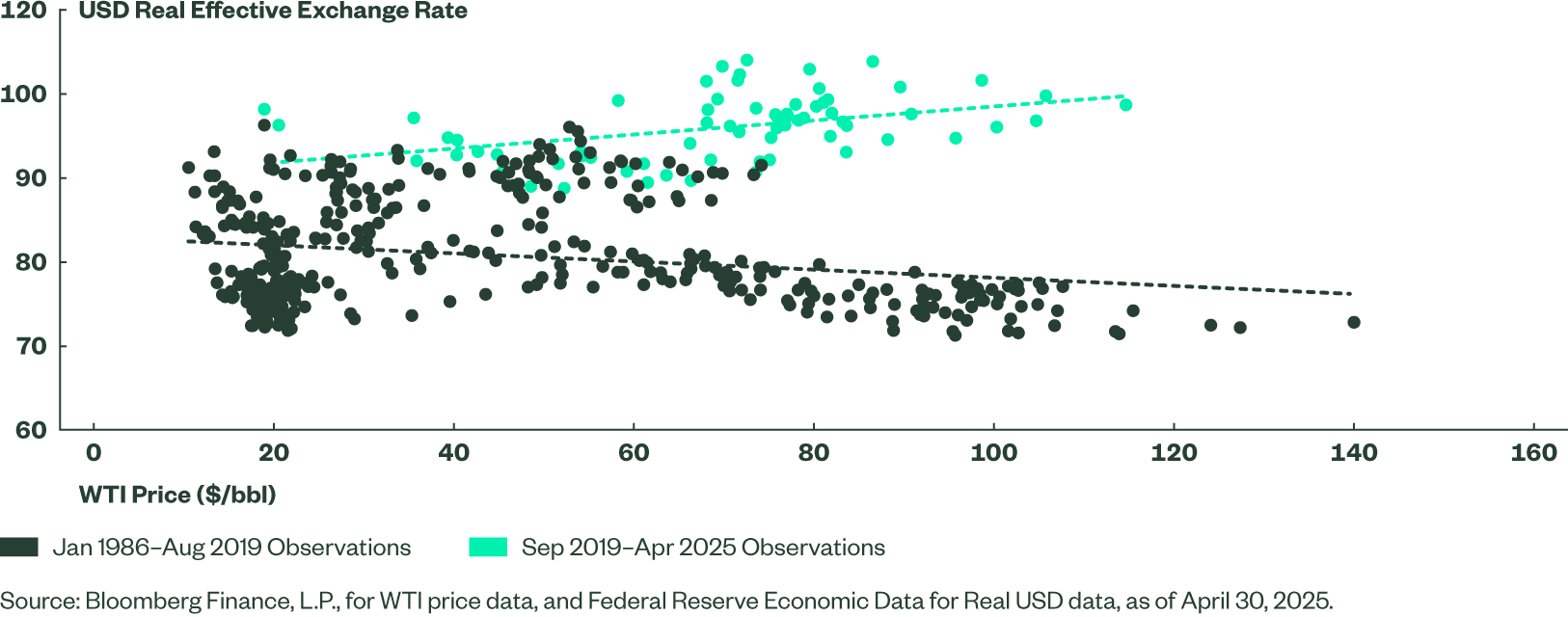

Finally, the US is pursuing a policy mix that could structurally depreciate the US dollar in coming years. For the Gulf, the combination of weaker oil prices, lower government revenue, and higher borrowing costs could also encounter higher inflationary pressures given the region’s high share of imports in its inflation indices. This is part of the rewiring of the historical inverse correlation of oil prices and US dollar strength (Figure 2). So, the Gulf disproportionately benefits during cyclical upturns, and now will disproportionately suffer from cyclical downturns.

Figure 2: Oil-dollar Correlation Pre- and Post-2020

Oil Price vs. USD Real Effective Exchange Rate

To a degree, some of this may be offset by helping non-oil exports grow in the region with improved competitiveness. Multiple years of investment in non-oil industries could now enjoy a tailwind from a weaker exchange rate.

Investment Implications

In the short term, GCC borrowing costs should mirror the changes in the US, with a steeper yield curve driven both by rate cuts on the shorter end and higher term premia on the longer end. Oil prices likely will continue to stagnate until the full effects of the US trade policy have worked their way through the real economy.

That said, the long-term prospects for the GCC’s non-oil industries look better due to anticipated closer ties with US technology, a potentially weaker US dollar, and the prospects of a more stable, prosperous region overall.

To stay current on the latest tariff discourse, don’t miss our latest policy insights.