Are rate cuts off the table in Australia?

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and financial markets have largely priced out the prospect of near-term rate cuts following an upside surprise in the Q3 CPI release. While headline inflation printed at 3.2% y/y, it’s worth noting that 0.6 percentage points of this came from utility bills, as households absorbed higher electricity costs after rebates expired. Although disinflationary forces are fading, we do not see significant underlying price pressures emerging.

The RBA’s post-CPI meeting adopted a modestly hawkish tone, as expected. The Bank acknowledged inflation risks but stopped short of signalling the end of the easing cycle. Markets, however, have shifted decisively, with the consensus now anticipating no rate cuts in the foreseeable future. Still, the interplay between inflation and labour market dynamics warrants caution. Even if inflation returns to the 2–3% target range, the outlook for policy will hinge more on labour market conditions.

Labour market risks underappreciated

Our analysis highlights three labour market risks that have yet to gain significant attention but could influence policy in the months ahead:

1. Rising unemployment amid high participation

The unemployment rate eased 0.2 percentage points (ppt) to 4.3% in October, after it rose by the same magnitude in the last month. Despite the step-down, the rate is 0.6 ppt higher than it was 2-years ago and the 3-month moving average has steadily risen to 4.4% from 4% in December 2024. Furthermore, the participation rate remained unchanged at 67.0%, just shy of its all-time high, indicating that job-finding has become harder.

Hence we continue seeing the labor market tighter on the margin. Supporting evidence includes:

- ANZ-Indeed Job Ads fell 2.2% m/m in October (ANZ-Indeed Job Ads)

- Applications per job ad on Seek hit a new peak (Seek)

Furthermore, the September rise was concentrated among youth (15–19 years), whose participation surged nearly 3% to 57.9%. Youth unemployment climbed to 10.5%, the highest since November 2021. Though they represent less than 20% of the labour force, volatility in this segment disproportionately affects the headline rate. The October step-down seem to be driven by the same dynamics, where the youth unemployment rate eased back down to 9.6% but the participation remained at 57.8%, implying that more people are looking for work.

2. Structural shifts in employment

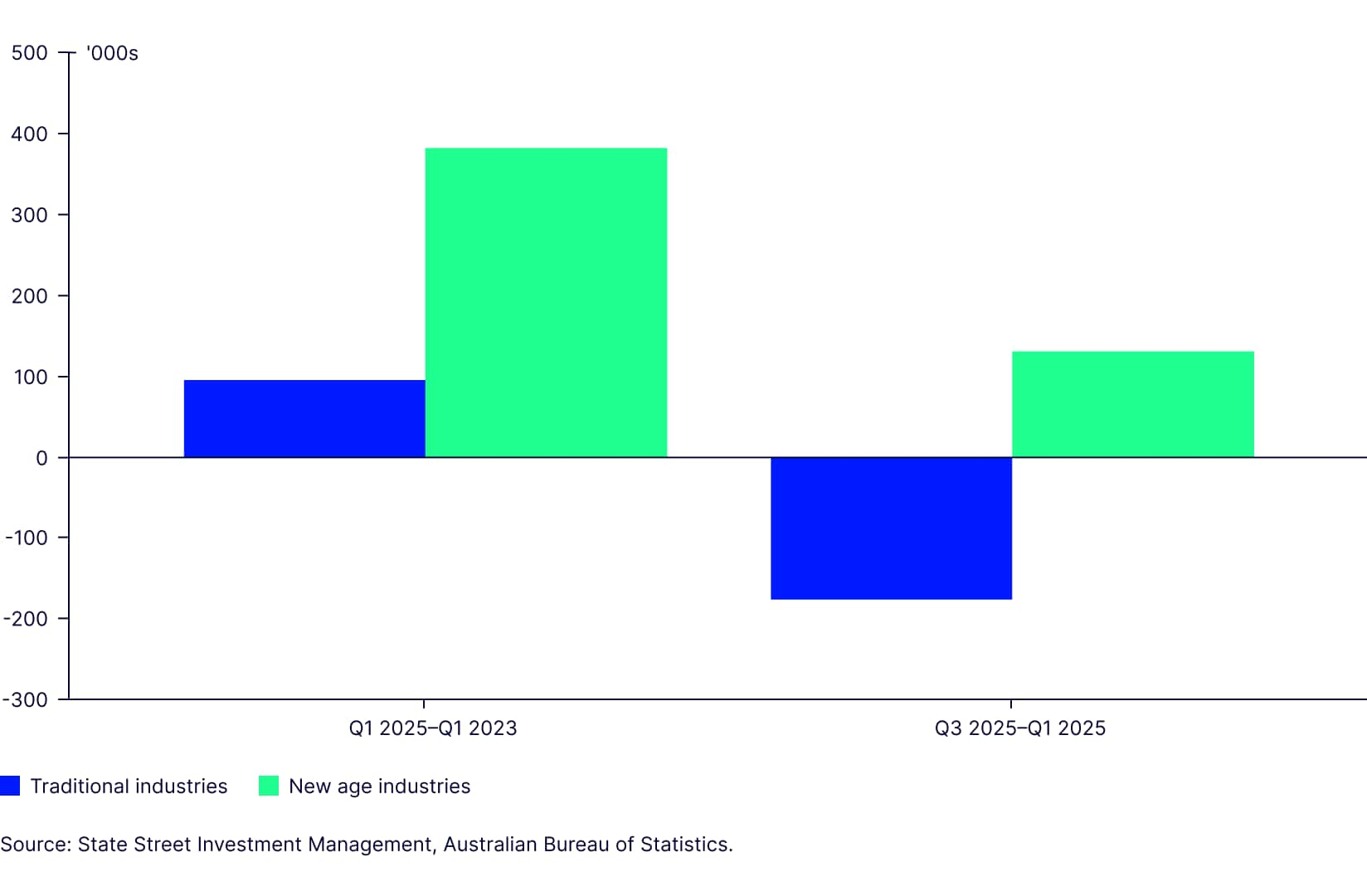

Additionally, this weakness has happened even as the new age industries that dominated job additions post Covid continue to do so (public administration, administrative services, education and healthcare & social assistance). This is because traditional industries (mining, manufacturing, construction and retail) that had added to employment between 2023-2025, are now losing jobs. These industries traditionally drove employment but have lost 175k jobs this year. This comes even as those that are driving employment have also slowed in employment creation (figure 1).

Figure 1: Traditional drivers of employment are struggling in 2025

Change in employment in Australia

- Manufacturing: Structural decline in the last many decades continues to persist (source)

- Mining: Facing weak investment, low commodity prices, and productivity challenges (source)

- Construction: Employment in the construction sector is slowing despite a national goal to build 1.2 million homes in the next five years. Contributory factors include higher costs & delays, financial stress & insolvencies and skilled labour shortages (source, source). An estimate is that the industry would need 90,000 additional workers by the end of 2025 and projected to rise to 130,000 by 2029

- Retail: The retail industry has been lowering employment on consumer spending weakness despite the improvements reported in recent times due to high cost of living according to KPMG. This is reflected in stagnant job postings and weak hirings. The Commonwealth government’s Jobs and Skills portal projects that employment will grow only 7% in the retail sector till 2035

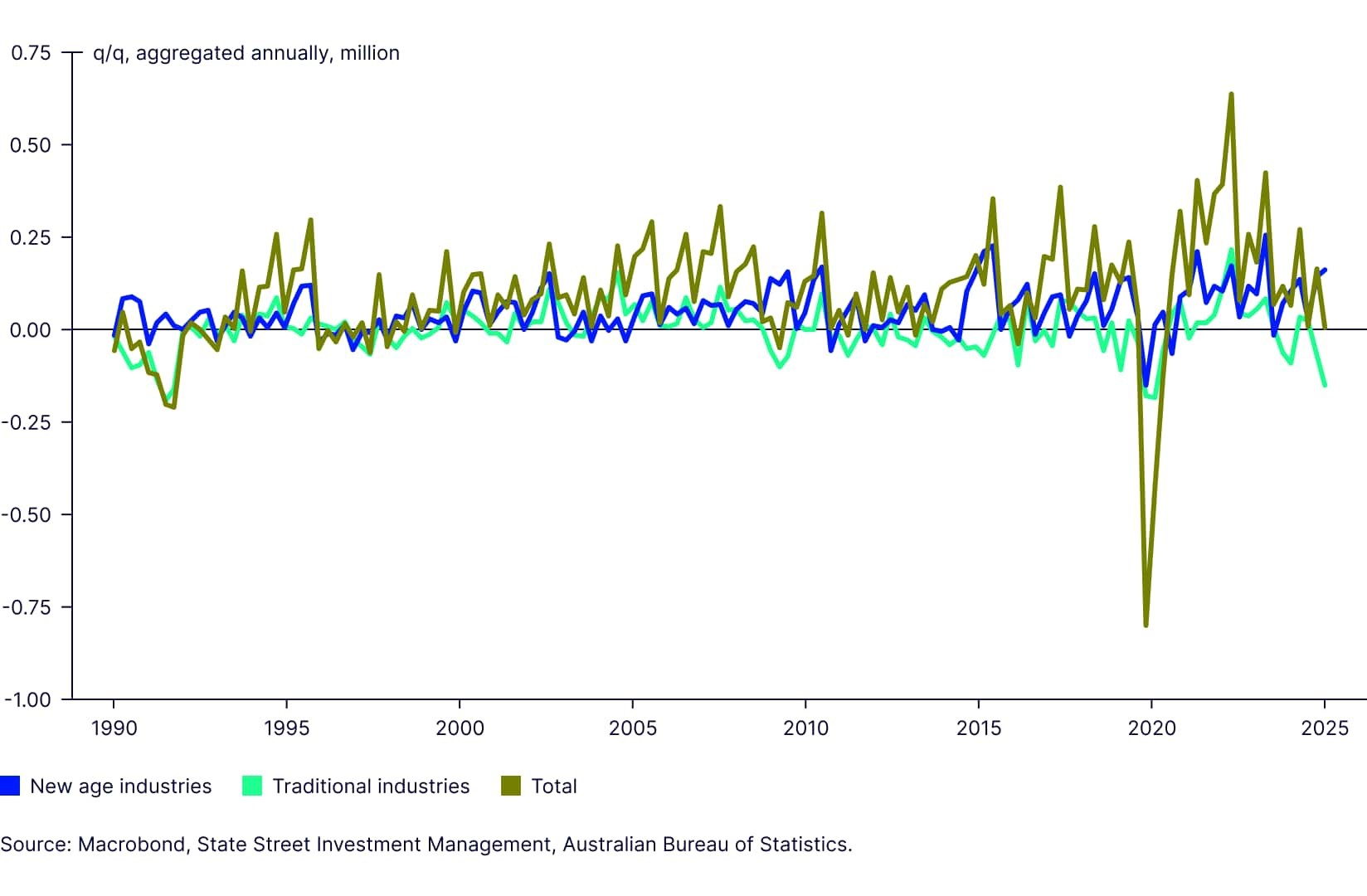

The momentum seems to have clearly shifted in the last year; when the quarterly change in employment is aggregated annually we are able to clearly identify a weakening trend (figure 2).

Figure 2: Employment trends in traditional industries is worrying

3. Leading indicators point to weakness

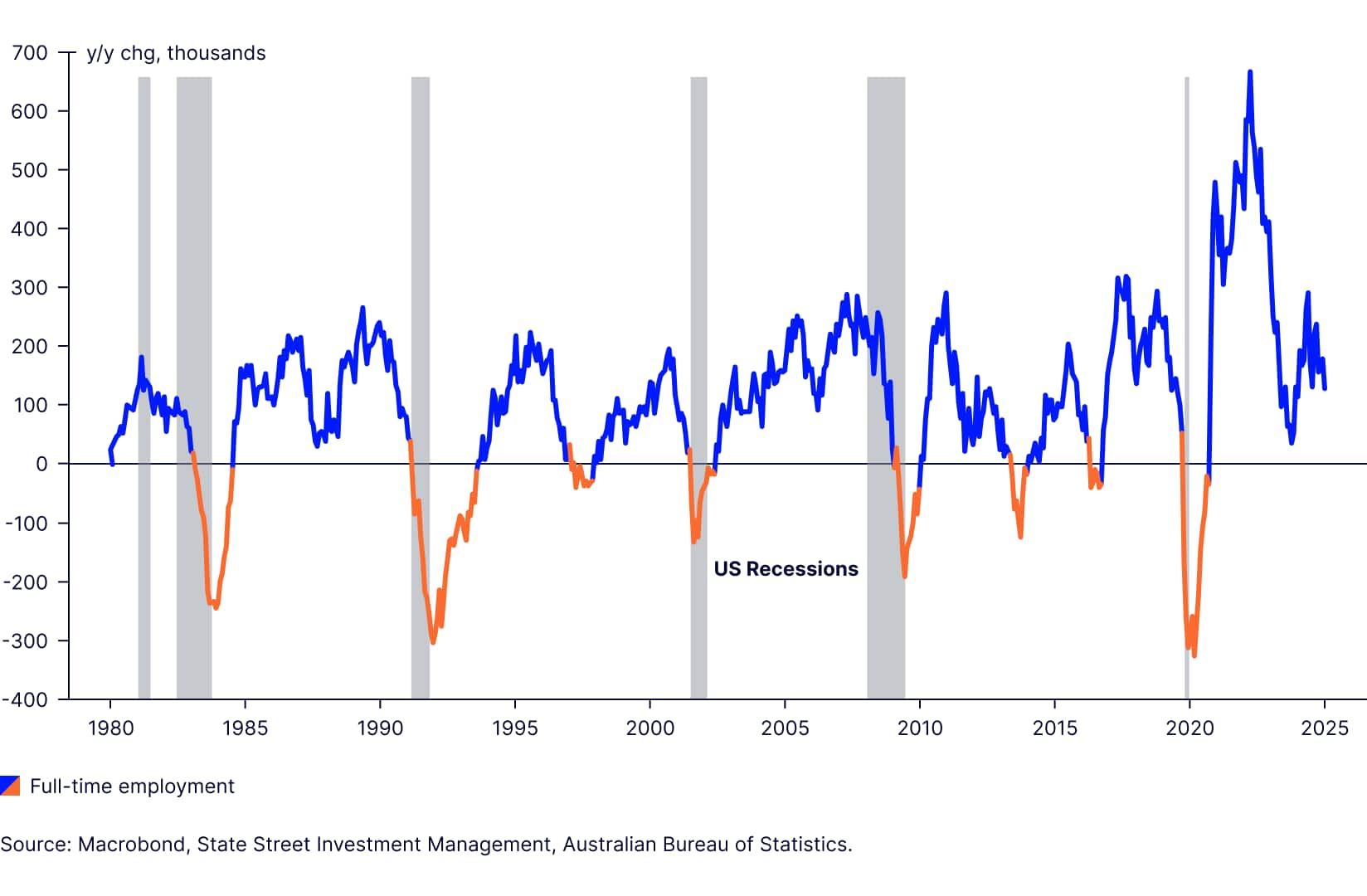

Roy Morgan’s unemployment measure, which leads ABS data by two months (with a 52% correlation), has been showing a consistent upward trend. Historical parallels with the U.S. labour market—currently experiencing significant layoffs—reinforce downside risks for Australia.

Figure 3: Australia’s full-time employment is cyclical

Inflation outlook: benign over the medium term

Despite the Q3 CPI surprise, Governor Michele Bullock emphasized one-off factors, including annual price reviews and rebate expirations. Structural drivers point to easing pressures:

- Widespread adoption of solar panels and the government’s Solar Sharer plan, offering free midday electricity, should lower energy costs next year

- Integration of renewables into the grid will further support disinflation, particularly in densely populated regions

- The impact of one-time price reviews would drop from Q4, while inflation in housing excluding utilities might remain benign

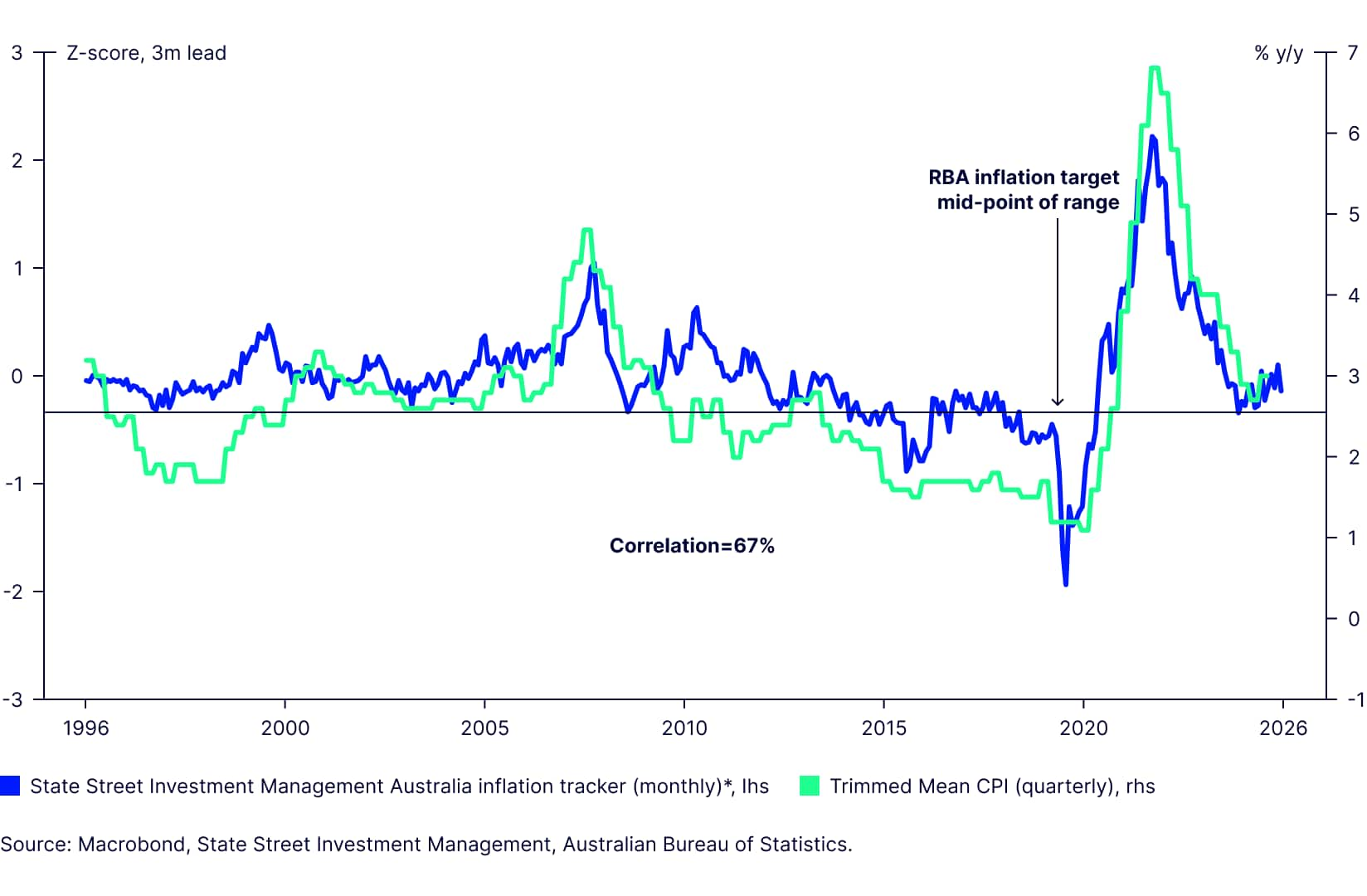

- Moreover, our State Street IM Australia Inflation Tracker is not signalling any imminent price-pressures in the pipeline, but that the RBA’s preferred inflation metric could likely move sideways in the near-term (figure 4)

Figure 4: Mild price pressures in Australia in the near term

So, even though the Q3 bump will numerically lift inflation in base effects, we do not foresee any significant surprises.

Policy implications

The RBA remains more focused on managing inflation and less on the softening labour market justifying its cautious stance. While markets have interpreted that as expecting no further cuts, a material deterioration in employment could prompt a policy pivot toward accommodation. While we do not expect a material deterioration, we cannot rule that out and hence caution on entirely pricing out rate cuts. Our view is that this is a pause in the rate cutting cycle rather than the end.

Investment implications

Growth in Australia has been improving modestly, driven by strong public investment and a rebound in housing construction. However, consumption has been subdued, suggesting this pickup in growth is unlikely to gain more momentum. In contrast, global growth prospects have improved as the geopolitical and trade policy uncertainty earlier in the year has materially reduced as several trade deals have been announced.

With the global outlook improved and no obvious catalysts for domestic growth, Australian investors should seek globally diversified portfolios. In practice, this means tilting portfolios to have a lower home bias, particularly in equities. Diversifying across asset classes including Australian fixed income and gold will also help investors deal with the still considerable uncertainty in global markets.