The income squeeze: How market concentration is reshaping equity returns

Discover how rising market concentration in US equities is driving strong returns but causing income from dividends to hit historic lows.

The US equity market has never been more concentrated. The top stocks make up an astounding 38% of overall market capitalization—more than double the 17% from a decade ago and compared to 23% from the turn of the century.1 While this concentration has driven strong returns, it has also eroded the market’s ability to generate income.

Income’s shrinking role in equity returns

Over the past 55 years, broad US equities have delivered an average annual total return of 9.9%,2 with 7.7% coming from price appreciation.3 That means dividend income contributed 215 basis points (bps), or 21%, to the total return.

This long-term average masks a significant shift in the current income landscape. On a rolling five-year basis, the income return has not been above 200 bps since 1998 (Figure 1). Even after a modest rebound in the mid-2010s, income’s contribution is approaching all-time lows.

The shrinking income contribution is largely due to today’s historically low dividend yields. The US equity market’s trailing 12-month dividend yield stands at just 1.15%, in the bottom second percentile of historical observations4 and just 10 bps away from an all-time low. And the rolling trend continues to decline (Figure 1).

Importantly, the current yield on equities is below both the current inflation rate (2.9% CPI year-over-year)5 and five-year inflation expectations (3.4%).6 This means equities are now delivering negative real income, a trend likely to persist if yields and inflation expectations remain where they are.

Sector shifts impact today’s low income

Blaming equities’ low-income returns on low dividend yields is just part of the story. The real driver is the changing composition of the equity market.

In 1990, the top three sectors by index weight were:

- Energy: 14.83% weight, 4.1% yield7

- Industrials: 13.73% weight, 3.4% yield8

- Consumer Staples: 13.07% weight, 2.5% yield9

Together, the top three sectors had a combined weighted dividend yield of 1.41%—higher than today’s whole market dividend yield of 1.15%.10 And today’s top three sectors’ weighted dividend yield is just 0.44%—largely due to the Information Technology sector, which makes up 33.9% of the index, having the lowest yield of all 11 GICS sectors, just 0.5%.11

Interestingly, both today and in 1990, the top three sectors contributed roughly 38% of the market’s total dividend yield. The difference is that in 1990 those top three sectors accounted for only 42% of total market capitalization, compared to 60% today. This shift illustrates how greater concentration has dampened income generation.

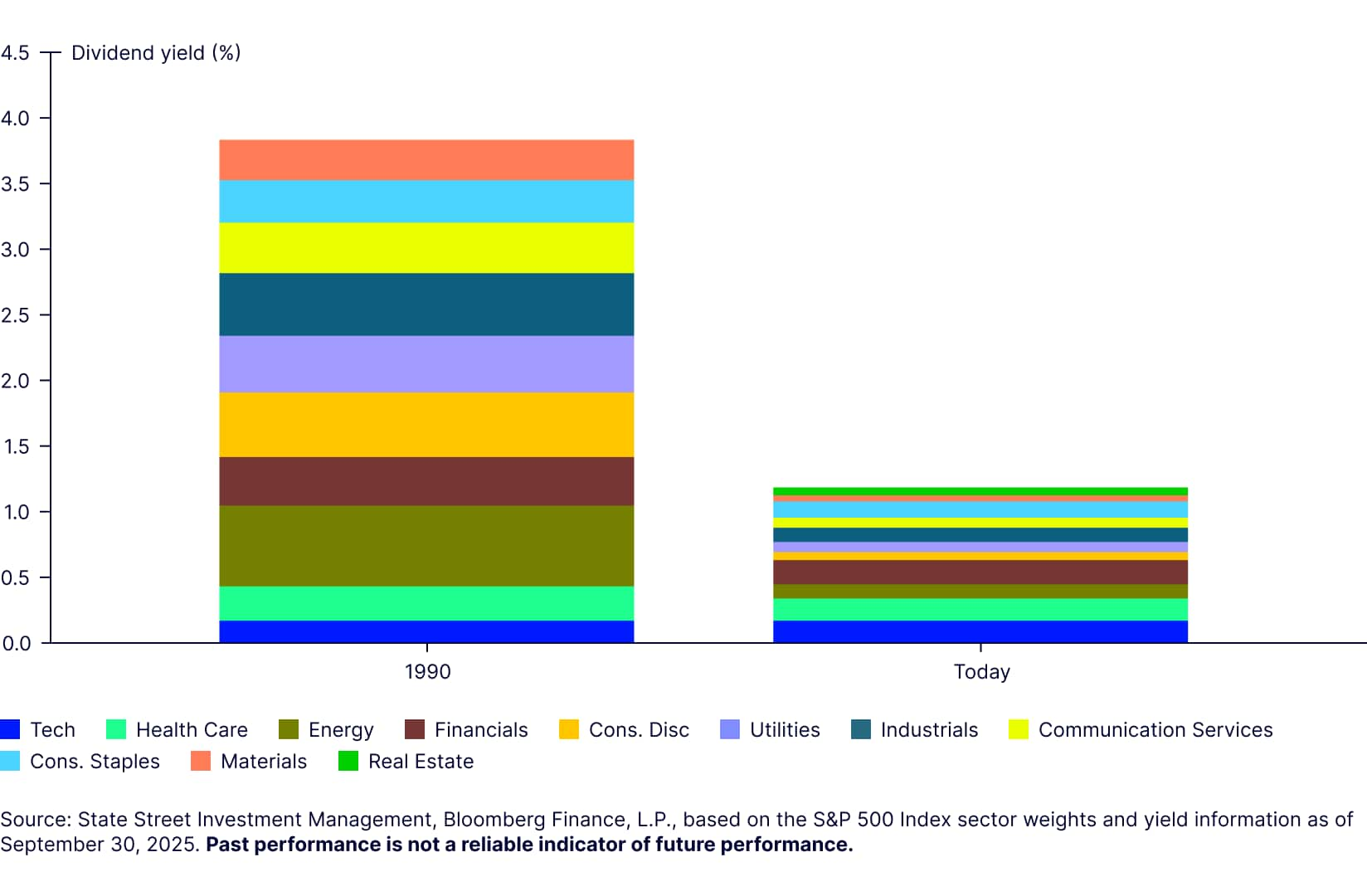

Today’s lower income is also more narrowly sourced compared to 1990 (Figure 2). Now even traditionally high-yielding sectors like Utilities, Consumer Staples, Energy, and Financials contribute little—not because of low yields, but because their market cap weights have shrunk. In fact, Utilities, Consumer Staples, and Energy each make up less than 5% of the Index, despite offering yields above 2.5%.12

Figure 2: Income contribution by sector

What if sector weights had not shifted?

The decline in income from equities isn’t about just lower yields—it’s also about which sectors dominate the market today. To isolate this effect, we can look at two hypothetical scenarios:

- Fixed 1990 weights: For example, if we kept sector weights constant (e.g., the Energy weight at 14.8%) but used actual dividend yields over time, the resulting yield would be consistently higher than what the market has delivered.

- Equal weighted yield: Giving each sector the same weight removes the impact of market cap shifts and also results in a higher yield than the actual market yield.

Both theoretical yield profiles exceed the actual realized yield on broad equities since 1990 (Figure 3).

Given that in each time series the same yield data for each sector is used, but the market cap weights are adjusted, the logical conclusion is that sector composition has been a primary driver of equities being sapped of income potential.

Buybacks dominate dividends, impacting income

The way firms return shareholder value has compounded the drop in income.

In the 1990s, S&P 500 companies paid out an average of 46% of their earnings as dividends.13 Today, that percentage is just 30%, as firms increasingly favor share buybacks over dividends.14 While buybacks can support share prices and total return, they don’t provide the steady, predictable cash flows that income-focused investors—particularly retirees—depend on.

Notably, up until 2005, S&P 500 firms returned nearly the same amount of capital through dividends and buybacks.15 But as firms started to realize the benefits of buybacks from a financial flexibility and tax efficiency perspective, buyback amounts began to outpace dividends.

In the past 12 months, US companies have spent almost $1 trillion on share buybacks, compared to $700 billion in dividends.16 While both figures are substantial, concentration effects continue to impact the market’s income profile.

The top 10 firms by market capitalization were responsible for 33% of total buybacks, while they accounted for just 13% of total dividends (Figure 4). This imbalance underscores a key trend of buybacks outpacing dividends. As a result, the S&P 500 buyback yield has consistently exceeded the S&P 500 dividend yield, which poses a challenge for income-oriented investors who rely on steady distributed cash flows.

How to adjust portfolios for declining dividends

Given income has historically contributed 200 bps to annual returns and that contribution is now lower, future total returns may fall short of historical averages. For US equities to maintain past performance levels, earnings growth will need to do more of the heavy lifting. And right now, that earnings growth is priced at extreme highs—setting the bar high to outperform expectations.

This will lead income-oriented investors—a demographic that’s growing as more people enter retirement—to look beyond broad US equities to a more diversified set of income-generating assets, including:

- Non-US markets: The yields for developed ex-US (2.8%) and emerging markets (2.4%) are structurally higher than US markets17

- High dividend equities: Strategies focused on high dividend paying stocks may deliver dividends by taking on some factor (e.g., Value) or sector-specific risks (unless sector neutral)

- Derivative income: Although they cap some upside potential, using options (typically selling calls) on sector ETFs can generate extra income

- Hybrid income: Non-traditional markets like preferred stocks and convertible securities combine equity and bond risk profiles

- Active credit: High income active credit strategies blend below investment-grade segments like senior loans, fixed rate high yield, and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) to pursue income with an equity bias, given high yield bonds often move in the same direction as US equities (with a beta of 0.45).18

In short, because broad US equities are no longer a reliable source of income, investors should consider rethinking the type of risk they’re willing to take and diversifying across a broader set of income-generating assets.

For more insights check out our market trends page.