What to Know About the Dutch Pension Reform

The Dutch parliament has approved the largest-ever pension reform in the Netherlands, requiring the transition from defined benefit (DB) to defined contribution (DC) pensions. Pension schemes will have until 1 January 2028 to comply with the new regulation. With over €1.2 trillion in accrued benefits, it could have significant implications for asset classes and investors.

Background

After many years of debate, the Dutch parliament has approved the largest-ever pension reform in the Netherlands, known as the Future of Pensions Act ‘Wet toekomst pensioenen’ (Wtp), requiring the transition from defined benefit (DB) pensions to defined contribution (DC).

Importantly, unlike similar shifts from DB to DC globally, it is not only future pension savings that will become DC, but existing DB assets will also transition. It is likely to bring about changes in the way Dutch pension funds manage their assets, and with over €1.2 trillion in accrued benefits it could have significant implications for asset classes and investors. The regulation came into force on 1 July 2023 and pension schemes will have until 1 January 2028 to comply with the new regulation. Within this period, funds are expected to share their transition plan with the De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) by January 2025, stating what should happen to accrued benefits and the type of contract for accrual, and their implementation plan by July 2025.

Pension funds have the choice to run the old and new pension pots in parallel. However, a survey by DNB suggests that pension funds accounting for 97%1 of total participants will choose to convert the existing pension pot into the new system.

Solidarity and Flexible

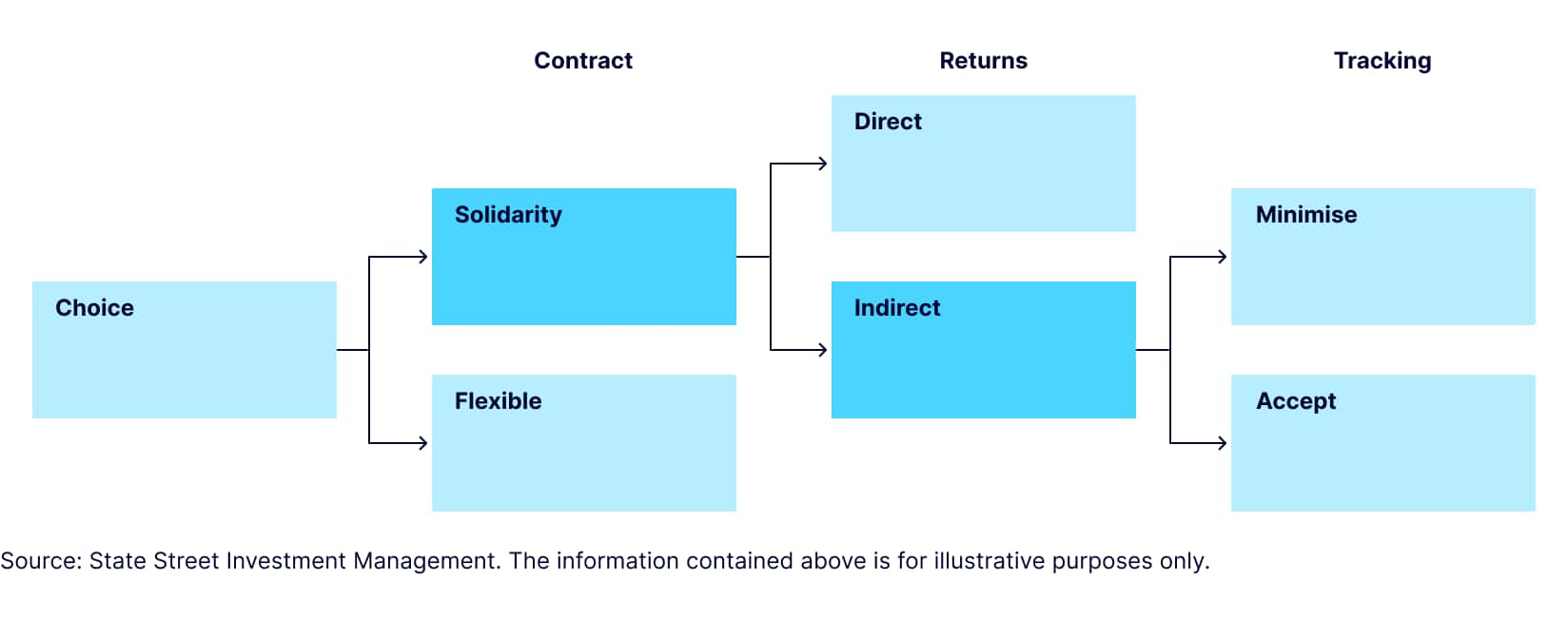

In the new system, pension funds can choose from two contract types — solidarity and flexible. The flexible contribution agreement resembles international, traditional DC schemes, where each participant has their own asset pool, which offers flexibility of investment choices.

The solidarity contribution agreement has a collective investment pool, where participants have exposure to hedge and excess returns. Hedge return is the return participants receive for a change in the projected benefit, driven by a change in interest rates. Excess return is the return generated by investing in risky or return- assets.

The exposure varies depending on the age of the participant — young participants have the highest exposure to excess return, whereas old participants have more exposure to hedge return.

Under the solidarity contract, pension funds can choose between two methods to determine the hedge return for participants — the direct or the indirect methods. The indirect method assigns theoretical returns to age cohorts based on the change in interest rates, regardless of the performance of the hedging assets. The return left after allocating hedge return is the excess return; i.e. any mismatch between the actual hedge and the hedge return contributes to or detracts from the excess return.

In the direct method, pension funds have two separate portfolios (hedge portfolio and return portfolio). Participants receive returns based on their exposures to these portfolios — there is a one-to-one link between actual and assigned returns.

It seems there is a clear consensus forming for the solidarity format. While the corporates might prefer flexibility, as it moves the most risk to the individuals, the unions have a big say in the Netherlands, and as solidarity is viewed to better protect members and be closer to the current DB set up, it has become the preferred approach for the majority of pension assets.

Within the solidarity format, there is also a clear consensus for the indirect method of returns. Arguably the direct method is a better fit for the existing portfolios from an investment point of view — i.e. hedge and growth portfolios are separate. However, it has more of an administrative burden and hence indirect is preferred. Consequently, pension funds will have to decide how they want to manage the hedge portfolio — whether they want to minimise the mismatch or accept, even target some mismatch to create excess returns in the hedge portfolio.

Figure 1

There are also some changes that apply to all pension funds irrespective of the contract set-up. The pension reforms will introduce so-called lifecycle investing. Lifecyle investing introduces an age-dependent portfolio. In short, the risk of the portfolio decreases with age and the allocation to the hedge portfolio will correspondingly increase.

Also, the capital requirements framework will be abolished. This will have implications for the attractiveness of different investments, including those frequently found in pension funds’ hedge portfolios, because they do not require any capital to be held against them — e.g., AAA EUR government bonds.

Key Considerations

Interest Rate Hedging

Over the last few years there has been an increase in hedge ratios from Dutch pension funds, in part due to the significant increase in interest rates that has occurred globally, making it an attractive time to increase hedges, and in part to protect coverage ratios ahead of the pension reform transition.

In order to transition to the new framework, pension funds need to demonstrate an attractive DC pension projection for the employees, to replace their DB-guaranteed income, which requires a coverage ratio of at least 105% in the old framework — hence creating the incentive to reduce risk by increasing hedge ratios and protect against falling interest rates ahead of the transition.

Interestingly, however, the pension funds also have exposure to equity, which is not widely hedged with equity downside protection, something that could be worth considering for funds with a lot of equity exposure.

It is highly likely that this increasing of hedge ratios has happened broadly and most pension funds are at their target hedge levels ahead of the transition, which, on an average, is approximately 70%.2 How pension funds intend to manage their hedges post transition varies across different pension funds and sectors.

Certainly, the concept of lifecycle investing can be interpreted as a reduced requirement for longer-duration hedging, as pension funds can choose asset allocations that specifically meet the investment objectives of different age participant groups. This allows pension funds to choose higher hedge ratios for old participants and lower ratios for young participants and, in turn, switch from hedging all liabilities to hedging predominantly shorter-duration liabilities (of retirees). In theory, this would lead to reduced demand for and selling of the long end and, in turn, steeper interest rate curves.

In practice, however, it is becoming apparent that, on the whole, and for the majority of pension assets, it’s unlikely pension funds will make material changes to their existing asset mix for several reasons:

- Just because the pension system is changing from DB to DC does not necessarily mean the investment philosophy of the pension funds is changing, and therefore pension funds that currently hedge the longest liabilities, may well continue to see merit in doing so.

- Indeed, there are some pension funds that have already chosen to have less hedging in the >30 year tenors in the existing framework – with less supply in longer tenors, that part of the curve is less liquid — and so there is less long end hedging for these schemes to remove.

- The majority of the assets in the pension funds are the older members, who have been saving for the longest, so when dividing the pension assets into cohorts, a greater proportion will be allocated to older cohorts which require more fixed income, resulting in a similar asset mix before and after transition.

- Pension funds are, thus far, predominantly focused on and concerned about the risks associated with the administration of the new pensions. The complexity of and risks associated with moving to the new system are at the forefront and are likely to remain so for the transition.

- Pension funds are aware of the market stress that could result from large trading programmes, and in turn the transaction costs associated with them, which is something they would want to avoid.

It is likely, therefore, at least for the initial transition into the new system, that pension funds will do so with limited impact to their existing asset mix, and we should not expect a “big bang” approach.

That said, there are funds that will be outliers to this approach, and there have been transition plans submitted that clearly signpost a large shift in the hedge ratio level and duration — particularly relevant to funds which have employees in the youngest cohorts only. These funds, whilst sizable, are small relevant to the total size of the Dutch pension fund liabilities, so would be unlikely to make a significant impact on market levels. The EUR rates market is large and liquid, and with insurance companies providing the natural other side to the potential Dutch pension fund flow, it should be able to digest such trading in normal market conditions, if it is approached in a sensible manner by the parties involved.

Leverage

It seems the use of leverage in the new framework is not given a lot of consideration. Utilising the permitted leverage could enable funds to generate excess returns, while also locking in hedge returns for younger members. Given where yields and solvency ratios are, this could be an attractive option and achievable with the use of leverage.

Cashflow Matching

The new framework can be thought of as two phases, the growth phase for the younger and the annuity phase for the retired. In the flexibility format, pensioners can choose to buy an annuity or keep investing. Whereas in the solidarity format, it is kept invested in the fund — i.e. the outcome in theory can be variable over time depending on returns. There is a consensus that there is a clear benefit for schemes to fully hedge the pensioner liabilities, to effectively create an annuity-like return in retirement.

A sensible way to approach this would be to manage the portfolio like an annuity book — cashflow matching the retiree’s theoretical hedge return. A pension fund can build a portfolio that delivers the cashflows, either with risk-free assets and minimal “mismatch” or with assets that also provide a spread, thereby contributing to excess returns. It may also make sense to include some inflation protection.

Inflation

There is an opinion among some that the reform has missed a good opportunity to better incorporate inflation protection.

In the growth phase, investment will likely be heavily into equity, which has an indirect linkage to inflation, and inflation-linked assets can also be considered as part of the portfolio. In the annuity phase, however, with the portfolio invested in fixed government bonds/credit/swaps, in order to provide the fixed liability cashflows, there will be zero inflation protection. Given the expected time in retirement is greater than 20 years, that is a long period without inflation indexation.

While it is not explicitly part of the new framework to provide inflation protection in retirement, it is possible to achieve this, depending on the format chosen. It is more straightforward with the direct method of returns, as participants receive the returns of the hedge portfolio, which could include some inflation-linked assets, while with the indirect method of returns, inflation-linked assets in the hedge portfolio would contribute to the excess return rather than the hedge return. With the indirect method is seemingly preferred by the majority, it will be interesting to see if pension funds are able to incorporate inflation protection and in turn whether the employees and unions are satisfied with the changes.

Timing of Transition

There are some pension funds that are ready to transition at the beginning of 2025. However, the expectation is that many will choose to wait and see how the transition goes for others before they make the move. Some want the pension administrators to be tested before taking the step. Many plans have submitted their transition plans, but there are also some that are still at the beginning of the process in deciding how they will implement the regulation, so there is a wide variation in the readiness.

Regardless of this, the DNB will still need to review and approve all the transition plans, and this could be a potential bottleneck, leading to deadlines being pushed back. It is also a reason for some funds to wait and see, to see the DNB response to some transition plans and what is approved or rejected.

From a market perspective, however, if a pension fund does in fact want to make significant changes to their portfolio, there should be a first mover advantage in terms of market moves — it makes sense to transition sooner rather than later. If there is little change to the portfolio expected, then there is no first mover advantage to be gained.

Instrument Selection

The removal of capital requirements impacts attractiveness of assets in the new framework versus the current framework. One area where this stands out is currency hedging. Historically funds had to hold capital against non-EUR assets if not FX-hedged, leading to the Dutch pension funds being big users of the FX forward markets. In the new framework, this capital charge will be removed and, given that often currency hedges can be seen as a drag on foreign asset performance, we could see more funds choosing not to hedge their currency risk, or reduce it.

The change will also impact other asset types; in the hedging portfolio we could see pension funds moving to higher-yielding, lower-credit-quality bonds to lock in higher spreads, with swaps still used as an overlay for longer-duration hedges where required. However, the choice of which swap to use also comes into question. ESTR is the EUR risk-free rate (RFR) and has the benefit of having the same floating index and discount curve.

However, in the old framework there was a capital requirement for the use of ESTR swaps and so the default preference for swaps for pension funds was 6M EURIBOR.

With that capital requirement no longer existing in the new framework, it may present opportunities for pension funds to trade ESTR swaps rather than 6M EURIBOR, if there is a benefit to do so. Another consideration here within the indirect returns method will be the pension funds’ appetite to take mismatch risk versus the DNB UFR3 curve., It is possible that over time as ESTR becomes more dominant and liquid, the UFR curve may begin to reference ESTR swaps.

Political and Regulatory Risk

There is a small political risk that there will be a referendum to vote against the reform, or at least there will be enough opposition to the reform that it is revisited in some respect. Given some funds have already submitted their plans and intend to make the transition early next year, this will become increasingly unlikely, as there would be a cost for any schemes that have transitioned to change what they have done. However, with little support for the reform in the new coalition, it is still a risk and the uncertainty that brings will likely result in more funds wanting to move towards the end of the timeline, potentially putting more pressure on the DNB.