Jumping Through Hoops: BoJ’s Path to Normalization What is the Road Ahead for Investors in Japan?

The Bank of Japan has relaxed its yield control policy, allowing more leeway for Japan’s bond yields. What does this mean for Japan’s monetary policy going forward and what are its implications for global investors?

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) will conduct a more flexible Yield Curve Control (YCC) policy from August by allowing the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yield to move beyond the current ± 50 bp. By offering to purchase 10-year JGBs at 1.0%, the central bank will in effect expand the upper limit of the band to +100 bp. While the lower limit of -50 bp will also be treated less strictly than before, the latest adjustment suggests some intentional asymmetry to the upside.

Specifically, the previous band of ± 50 bp is now considered as a “reference range, not rigid limit” (Figure 1). The Ministry of Finance subsequently raised its assumed interest rate for FY 2024-25 to 1.5% (from 1.1%) to calculate its debt servicing costs, raising the possibility of higher interest rates for longer in Japan.

This tweak is in line with our expectations and underscores Japan’s sound macroeconomic fundamentals. Japan’s 3-month annualized headline CPI of 2.4% is higher than that of the United States (US, 1.9%) and Germany (1.7%), but the country’s inflation has risen with a lag relative to other developed economies. Inflation is perceived in a positive light in Japan, and with a more tolerant BoJ, a better leg in Japan’s post-pandemic recovery is unfolding.

Inflation was anemic in the past three decades. In the ten years to 2010, prices in Japan declined by 2.7% compared with a rise of 26.3% in the US and a rise of 27.5% in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) economies. Consequently, there is less market confidence in the sustainability of the current bout of inflation. Even Prime Minister Fumio Kishida could not rule out the return of deflation in January – the very month when headline CPI growth peaked at 4.3% YoY. However, confidence is rising that this time is different.

The BoJ and the government recently upgraded their FY 2023 core CPI forecast sharply to 2.5% and 2.6% YoY, respectively, above the 2% central bank target. Expectations for FY 2024 are 1.8% and 1.9%, respectively, which reflect a minor technical adjustment due to base effects. Inflation may be slowing down ahead, but we do not expect the momentum to fizzle out.

Both expect GDP to grow at 1.3% and 1.2% in FY 2023 and FY 2024, respectively, quite modest at least for the current fiscal where actual growth could end up substantially higher. The economy grew at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 6.0% QoQ in Q2 against consensus estimates of 2.9%, driven more by external demand. Nonetheless, we still expect consumer spending to drive growth above the target inflation rate this year.

As far as investors are concerned, some of these developments have precipitated at least two key questions:

1) Is the current bout of inflation sustainable?

2) If so, what is the road ahead for investors?

Rise in Inflation May Not be Transitory

There are two key reasons why Japan’s inflation may continue to remain elevated: one is structural in nature and the other, more important one, is a change in the ‘price-wage setting attitude’ among firms.

1) Structural Causes

Japan’s consumer price index (CPI) rose 3.3% YoY in June, down a percentage point from its January high. Although CPI may have peaked this cycle, it is not on a deflationary path, primarily due to a fall in energy prices, which retracted by half a percentage point due to government subsidies. However, as these subsidies are getting gradually unwound, gas prices recently hit a 15-year high of ¥176.70. Prices of some sticky components are also ticking higher. In July, services inflation, often perceived as the stickiest in the CPI basket, rose to 2.0% YoY for the first time in 30 years.

Food prices, which have a 26.3% weight in the CPI basket, rose to 8.8% YoY in July, the highest since September 1976. Multiple food items scaled record highs – for example, medium-sized eggs are selling at ¥280 in Tokyo, down from ¥350, but still 46.3% above the historic average. As prices of most food components have climbed in the last year, we do not expect any further price rises, but the current elevated levels may stick due to robust demand. Furthermore, the high possibility of an El Nino this year could mean persistent inflation in food prices.

Housing CPI (21.5% weight) may also have shifted to a higher equilibrium. The prices of condominiums across Japan have risen while housing demand in cities remains elevated. The unit price in Tokyo’s central wards in July was ¥133.4 million, 80% higher than the average until 2022, on higher construction material costs. These prices are likely to persist due to high domestic migration, and housing CPI, which averaged 0.0% YoY between 2010-2022, has now risen to 1.2% in 2023.

2) Labor Market and Wage Growth

A more upbeat view of wage dynamics was the key reason for the BoJ’s YCC move in July. The cost of labor (wages) should rise during periods of high demand and low supply. However, despite unemployment rate hovering below 4% since 2014, total cash earnings growth (12M moving average (MA)) oscillated between -1.0% and +1.3% YoY.

The labor market continues to remain very tight with an unemployment rate of just 2.5%, the lowest among developed economies. Moreover, 84% of Japanese aged 25-64 are already employed, making further gains in participation hard to come by (Figure 2).

With persistent demand and labor scarcity, Japanese companies are finally raising wages. The seventh and final round of shunto wage negotiations resulted in 3.58% wage growth, including in seniority-based components, the highest in thirty years. Resultingly, the total cash earnings (12M MA) jumped 1.8% in June. We expect this trend to accelerate in the second half of this year as it will take some more time for the negotiated results to show up in data.

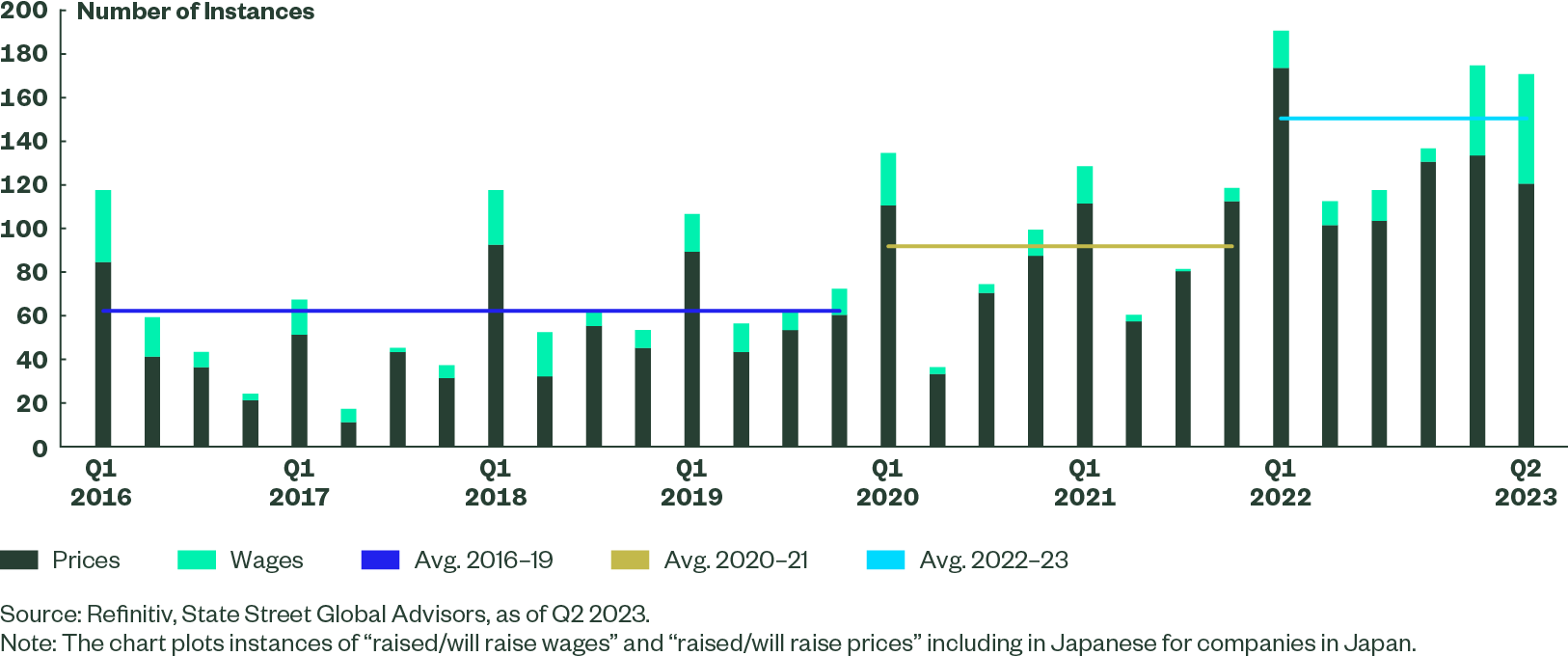

Not only are companies raising wages, but they are also providing forward guidance. The Nikkei collated some advertisements by companies that went to the extent of promising wage growth until 2030. Furthermore, an advisory panel of the labor ministry agreed to raise the minimum wage by 4.3% this fiscal to ¥1,002. In FY 2022, 62% of Japanese companies hiked salaries, up sharply from 38.7% in the previous year, while many have begun raising prices for the first time in decades. There is also a big jump in instances of ‘raised wages’ and ‘raised prices’ on the transcripts of Japanese companies (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Instances of Wage Growth/Price Rise See a Jump

Aggressive price rise in the fast-reviving tourism sector is also noticeable. Prices of the JP Rail pass, the tourists’ favorite train pass, will rise by a whopping 70% from October. Moreover, municipal accommodation taxes on hotel guests are also set to rise in different cities. In Kyoto, guests are required to pay a flat ¥1000, up five times in most cases.

The Road Ahead for Investors

With the BoJ relaxing the 10-year JGB yield band, the next leg of their policy normalization journey may have begun. Fundamentally, we expect the Japanese economy to continue to grow at a solid pace with a virtuous cycle between higher prices and wages taking shape. Additionally, the chances of a hard landing have diminished in the US and inflation is declining, which may allow the 10-year JGB yield to find its fair value at around 0.75%.

If this narrative plays out, we expect the BoJ to change the structure of YCC by targeting the 10-year JGB yield at 0.5% with a 50 bp/100 bp tolerance band by Q1 2024. This may mean that yields may remain in the same range or may move slightly higher. We still think that an outright removal of the YCC policy is improbable, given the policy’s centrality in managing Japan’s high government debt (258.9% of GDP in 2022).

If the Japanese and global economies are able to endure what could be a seismic shift in BoJ’s monetary stance, we expect the BoJ to move out of its negative interest rate policy and raise the benchmark short-term interest rate to 0.0% by H2 2024. For this to happen, the central bank would like confirmation of strong wage growth from next year’s shunto negotiations as well. Regardless, the path towards normalization is fraught with at least two key risks.

1) Risks Related to Market Functioning

The first risk is related to market functioning, which is reportedly improving. However, the JGB market still faces troubles as trades worth ¥18.4 trillion failed in June, the highest on record. These failures came after the formation of a ‘smoother’ yield curve as compared to last year, posing questions about the sustainability of the improvement in market functioning (Figure 4).

2) Risks Related to Tapering

A cat and mouse game is currently playing out in the JGB market as there might be participants who purchase 10-year JGBs solely to sell them to the BoJ. However, the key to stability in the bond market lies in a ‘gradual’ rise in bond yields. Indeed, the BoJ already intervened twice in the first week after the YCC tweak, with unscheduled purchases worth ¥300 bn (31 July) and ¥400 bn (03 August) when yields were at 0.60% and 0.65%, respectively.

We see these as speed breakers on the path to higher yields, but the equilibrium may well be below the 1.0% limit. This will continue until there is clarity regarding the maximum 10-year JGB yield that the BoJ would tolerate. However, should markets test the 1% level, the BoJ may intervene with large-scale JGB purchases, although we think the probability of this scenario is low.

An ideal solution would be more domestic institutional participation in the JGB market. The BoJ holds a whopping 53% of the JGBs and has purchased an average of ¥9.8 trillion worth of JGBs each month since 2022, nearly 25% more than the average until December 2021. As these purchases will slow down, the BoJ’s holdings may decline. In fact, the latest interventions amounted to just ¥700 billion, probably because the BoJ wanted to express some tolerance to rising yields while communicating the need for cautiousness (Figure 5).

The YCC tweak has resulted in higher yields across the curve, with the 30-year JGB now yielding 1.6% – 30 bp higher since the YCC tweak. This rise in yield might elicit some interest of domestic institutions, especially life insurance companies, thanks to higher hedging costs elsewhere. The Nikkei recently reported that seven out of nine life insurance firms considered the YCC tweak as a favorable factor for purchasing Japan’s ultralong government debt. Expectations of better participation will help curtail the rise in Japanese yields.

Either way, we remain hopeful that the BoJ will taper its purchase of JGBs, which at one point ended up being more than 100% of the issued JGBs. It is possible that the Japanese investors are likely more interested in the US Fed stopping its hiking than the BoJ letting yields rise beyond their comfort zone, which if proved right could mean lower volatility and a moderate rise in global yields.

A more worrying risk is higher global yields (and volatility) owing to a potentially fading Japanese bid for global bonds. Japanese investors are the biggest holders of US Treasuries and any sharp outflow could pose upside risks to yields. Japanese holdings of Treasuries had declined since the Fed started hiking last year, but buying resumed after the BoJ’s YCC tweak in December. Holdings and flows from Europe are smaller compared to that of the US, so risks to US yields are probably more pronounced than for Europe (Figure 6).

In Conclusion

Clearly, the BoJ has its task cut out with regard to policy normalization, having to deal with not so insignificant market risks detailed above. To be sure, the key lies in adopting a measured approach, which should ensure that global market volatility is under control. Finally, risks of a recession have declined but not disappeared in Japan. If a recession were to materialize, the normalization process will stall and will be pushed forward to a more salubrious period.