A Better Macro Policy Framework for Europe

The new EU fiscal rules and the recently updated ECB monetary policy framework are tangible signs of the region’s improving macro policy backdrop.

Last September, we outlined reasons why investors should revisit their long-standing underweight exposure to European assets. One piece of our argument was the improving macro policy backdrop in the EU. The new EU fiscal rules and monetary ECB operating framework, both announced in the first quarter, are tangible signs of this.

With these reforms, fiscal and monetary policy actions that had previously been implemented as one-off responses to crises, have now become forward-looking features of Europe’s macro policy toolbox . Neither reform is a game changer; however, they are steps in the right direction, enhancing the bloc’s ability to manage crises and strengthening its internal cohesion. They improve the sustainability of the Euro and, indeed, the European project as a whole.

The New Fiscal Rules Are Simpler and Account for Country-by-Country Differences

In early February, EU member countries agreed on long-awaited reforms to the EU fiscal rules.1 The reforms are fundamental insofar as they change both the rules themselves and how they are governed.

The prior rules emerged from the eurozone crisis of the early 2010s. Although observers still frequently refer to them by the two nominal limits set for EU members —a 3% of GDP budget deficit, and a 60% debt to GDP ratio—in practice, they were highly complex (both the rules themselves, and how they were applied). Their inability to deliver on the ultimate goal of ensuring fiscal convergence (or even preventing further divergence) made it clear that change was needed.

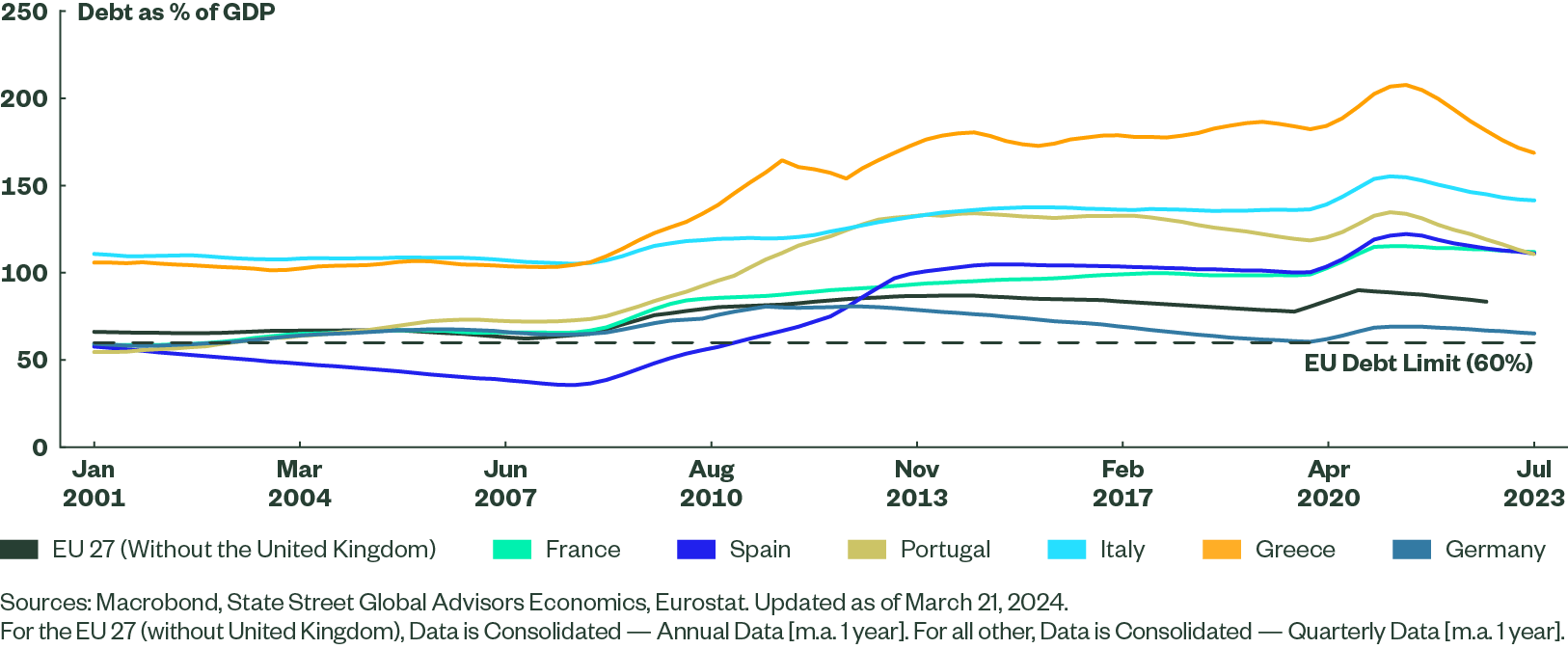

The top criticisms of the old rules were that they were too procyclical, too complex and too formulaic.2 The new rules are simpler, less procyclical, and therefore more credible and more effective than the old ones. However, building consensus around the new rules took almost a decade, partly because varied debt levels among EU countries meant that one size of reforms did not fit all (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Higher Debt Levels Post COVID-19 Coud Spur Fiscal Consolidation

The Specifics of the Revised Rules

The fiscal reforms make two fundamental changes:

- Individual countries have more ownership of their specific fiscal consolidation paths. While previously, countries had to follow a one-size-fits-all path defined by the Commission, the new rules recognise that what is fiscally sustainable can differ among countries. The new fiscal paths will therefore be individually negotiated on the basis of a debt-sustainability assessment that takes a holistic view of a country’s circumstances.

- Rules are simplified. If compliance was previously judged on multiple fiscal indicators, the new rules focus on just one – net expenditure.3 The chief benefit of using this one metric is that it is observable and thus easier to monitor. The overarching idea is that a simpler, looser, and more flexible approach is a better way to manage fiscal risks within the Union.

This is not to suggest that the conservative “Nordics” have capitulated to the profligate “South”. The new rules include a wide range of limits, for example, on the minimum size of the annual fiscal adjustments. What is different is the shift in emphasis. The intent is clearly to reduce the extent of micromanagement by the European Commission. However, the limits prevent the path-setting exercise from becoming a fiscal free-for-all.

Market and Economic Impacts

In the short term, a drag on growth is inevitable, but not because of the new rules; rather, despite them. Since the EU suspended its fiscal rules in 2020 due to the COVID-19 crisis, member states have run fiscal deficits far in excess of the new rules. A fiscal adjustment would have at some point occurred regardless.

In the long term, the effect is more uncertain, but net positive. Most importantly, the reforms strengthen the integrity of the euro and, by extension, the EU itself. They do so in three ways: (1) by modernising the rules to reflect current political priorities; (2) by reaffirming the political commitment to fiscal prudence; and (3) by making it more likely that in a crisis, calls to support the integrity of the bloc will trump concerns over moral hazard.

All else equal, we expect this reform to soften regional business cycles and reduce the likelihood that countries will drop the euro. This is good for both European assets and the euro in the long run.

Gaps to Be Aware Of

Even though we see positive impacts on long-term growth, we note the following headwinds to the effectiveness of the rules:

- Year 2027 may have a cliff effect. Starting from 2028, countries must include interest expenses in their calculations of net expenditure. This leaves fiscal space for highly indebted governments today, but it could result in a fiscal shock later on, particularly if rates stay high.

- Power politics will continue to play an important role. The new rules do not change the political balance of power within the EU. Larger members will still be able to get away with more exemptions.

- Greater politicisation of the fiscal paths. Greater national ownership of fiscal paths implies greater influence from the shifting nature of national politics. Incoming governments have low incentives to follow through on fiscal commitments of the government they replace.

Moreover, there is a mismatch in timing. The fiscal paths negotiated with the EU will last for four years or seven years—longer than the two years that governments in Europe stay in power, on average.4 The problem could be worse in countries with a frequent government turnover. The fact that the new rules exclude national fiscal councils from meaningfully participating in the process is a missed opportunity to reduce this risk.

The New ECB Operational Framework Clarifies How Increased Liquidity Needs Will Be Met

Following a review initiated in December 2022, the ECB announced changes to its monetary policy operational framework on March 13. The intent is to ensure monetary policy responds to changes in the financial system such that it remains “effective, robust, flexible and efficient in the future.”5

Unlike the tight liquidity environment that prevailed prior to the Great Financial Crisis, there is now a commitment to a demand-driven, ample liquidity system, with the ECB supplying reserves in much larger amounts. The ECB will continue to provide as much liquidity as banks request in exchange for appropriate collateral. In this, the ECB is more “generous” than the Federal Reserve.

The ECB has maintained three policy interests rates, and they remain in place. Their roles are unchanged, but there is a slimmer “corridor” between the floor for banks seeking ECB funding (deposit facility rate) and the rate for short-term credit access (main refinancing operations) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The ECB’s Main Policy Rates Are Unchanged

Liquidity Tool |

Details on Rate |

Role |

Importance |

Deposit Facility Rate (DFR) |

Now 4% |

Main channel for policy implementation. |

The ECB has formally adopted a demand-driven floor system with the DFR as its policy rate |

Main Refinancing Operations (MRO) |

Now 4.5%. The corridor between the MRO and the DFR will be reduced from 50 to 15 basis points. |

Rate at which banks can access liquidity on-demand. Short-term funding rate. |

A slimmer corridor means less overnight rate volatility. |

Marginal Lending Facility (MLR) |

Now 4.75%. Unchanged 25 bp premium over the MRO. |

The cost of obtaining overnight short-notice funding.

|

Used in tandem with the other rates to ensure price stability |

These changes will become effective September 18. The commitment to a demand-driven ample liquidity environment and the narrower rate corridor should help reduce volatility in money market rates and reduce banking sector liquidity squeezes.

Future Guidance

The ECB Governing Council also laid out a set of principles to guide monetary policy in the future. Beyond the focus on effectiveness, robustness, flexibility, efficiency, and the support of a open market economy, the Governing Council also laid out a secondary objective for monetary policy. Specifically, “To the extent that different configurations of the operational framework are equally conducive to ensuring the effective implementation of the monetary policy stance, the operational framework shall facilitate the ECB’s pursuit of its secondary objective of supporting the general economic policies in the European Union – in particular the transition to a green economy – without prejudice to the ECB’s primary objective of price stability. In this context, the design of the operational framework will aim to incorporate climate change-related considerations into the structural monetary policy operations.”

It remains to be seen what this open acknowledgement of a preference to cooperate on broad objectives where appropriate between the two main macro policy branches will mean in practice. But given that for years, the ECB has conducted policy in ways that sometimes intruded on other areas—most obviously the fiscal sovereignty of member states—a more a generous interpretation of monetary policy conduct is another possible source of improved effectiveness that stems not from policies or rules themselves, but from how they are being implemented.

The Bottom Line

Long-term thinking is rare in politics. However, the multitude of crises that have beset the EU in recent years appear to have finally catalysed a new sense of pragmatism among European leaders. These changes to the fiscal and monetary policy frameworks should be understood as separate yet complementary efforts to enhance the effectiveness of macro policymaking in the region by allowing more flexibility and speed in addressing incoming shocks.

Implementation will certainly be imperfect, and there will be no shortage of criticism. That should not obscure the fact that these reforms are a net positive for the region.