Creating a Tax Efficient Portfolio with ETFs

- Among their many advantages — intraday liquidity, transparency, low cost and ease of use — exchange traded funds (ETFs) are also known for their tax efficiency.

- Australian ETF investors could receive franking credits where the ETF owns Australian shares.

- ETF investors may be eligible to receive up to half of the realised gains distributed by an ETF tax-free.

ETFs Can Minimise Tax liabilities from Capital Gains Distributions

Investors can seek to minimise the impact of capital gains taxes from distributions by choosing a tax-efficient investment product with low turnover, and a widely diversified underlying portfolio.

Among the many more obvious advantages — low cost, intraday liquidity, transparency and ease of use —ETFs are also known for tax efficiency. (Note that tax efficiency refers to how well an investment minimises an investor’s taxes while they own it). ETFs typically generate lower capital gains tax liabilities from distributions than active unlisted funds for four reasons:

- Low Portfolio Turnover. ETFs tend to have lower turnover than actively managed unlisted funds, which can reduce the realised gains that need to be distributed. Of course, different ETFs have different levels of internal turnover, so make sure you check the Product Disclosure Statement.

- Discounted Gains. Low turnover often means a longer holding period for each of the underlying investments. ETFs generally hold underlying securities longer than 12 months, which usually qualifies any gains that are realised for the long-term capital gains tax discount.

- Secondary Market Transactions. Unlike active unlisted funds, when ETF investors sell their units on the stock exchange to another investor, the ETF portfolio manager does not need to buy or sell any of the ETF’s underlying investments. So, unlike traditional active unlisted funds, one ETF investor’s sell decision has no impact on other investors, and capital gains distributions can be kept low. Active unlisted funds may need to buy or sell stocks every time an investor applies for, or redeems, units, which can generate higher capital gains distributions to all investors at year end.

- Primary Market Transactions. Sharemarket brokers who facilitate trading on the stock exchange sometimes create or redeem ETF units with the underlying manager. ETF portfolio managers do need to buy or sell stock for these “primary market” transactions. However, ETFs often have tax mechanisms in place to avoid passing any realised capital gains from this activity to the ETF’s investors at year end. These tax mechanisms are much more difficult to implement for active unlisted funds.

The unique structure of ETFs can reduce tax liabilities from capital gains distributions for tax-aware investors and allow for more assets to remain invested — typically increasing the growth potential of the investment.

The Advantage of Dividend Imputation

The dividend imputation system in Australia can represent an important advantage for investors over the dividend taxation schemes found in other countries because it largely eliminates the double taxation of corporate profits in Australia. If Australian corporate taxes have already been paid on profits used to fund dividends, those taxes need not be paid again at the personal level by investors.

The corporate taxes paid are attributed, or imputed, to the Australian investor through tax credits called franking credits. Franking credits can be used to reduce an investor’s total tax liability. For investors who are individuals or complying superannuation entities, any excess franking credits can also be refunded at the end of the year if the investor’s franking credits are greater than their tax liability.

Let’s look at an example. ABC Corporation makes $1.00 per share in pre-tax profit during a given period and would like to pay it all out in the form of dividends. After paying the 30% corporate tax, ABC Corporation distributes $0.70 per share in fully franked dividends. To the Australian investor, this is equivalent to being paid an unfranked, “grossed up” dividend of $1.00 per share. The 30% corporate taxes already paid will accompany the dividend in the form of a $0.30 per share franking credit and act similar to an “IOU” from the tax office.

From this we can see that:

Dividend + Franking Credit = Grossed Up Dividend

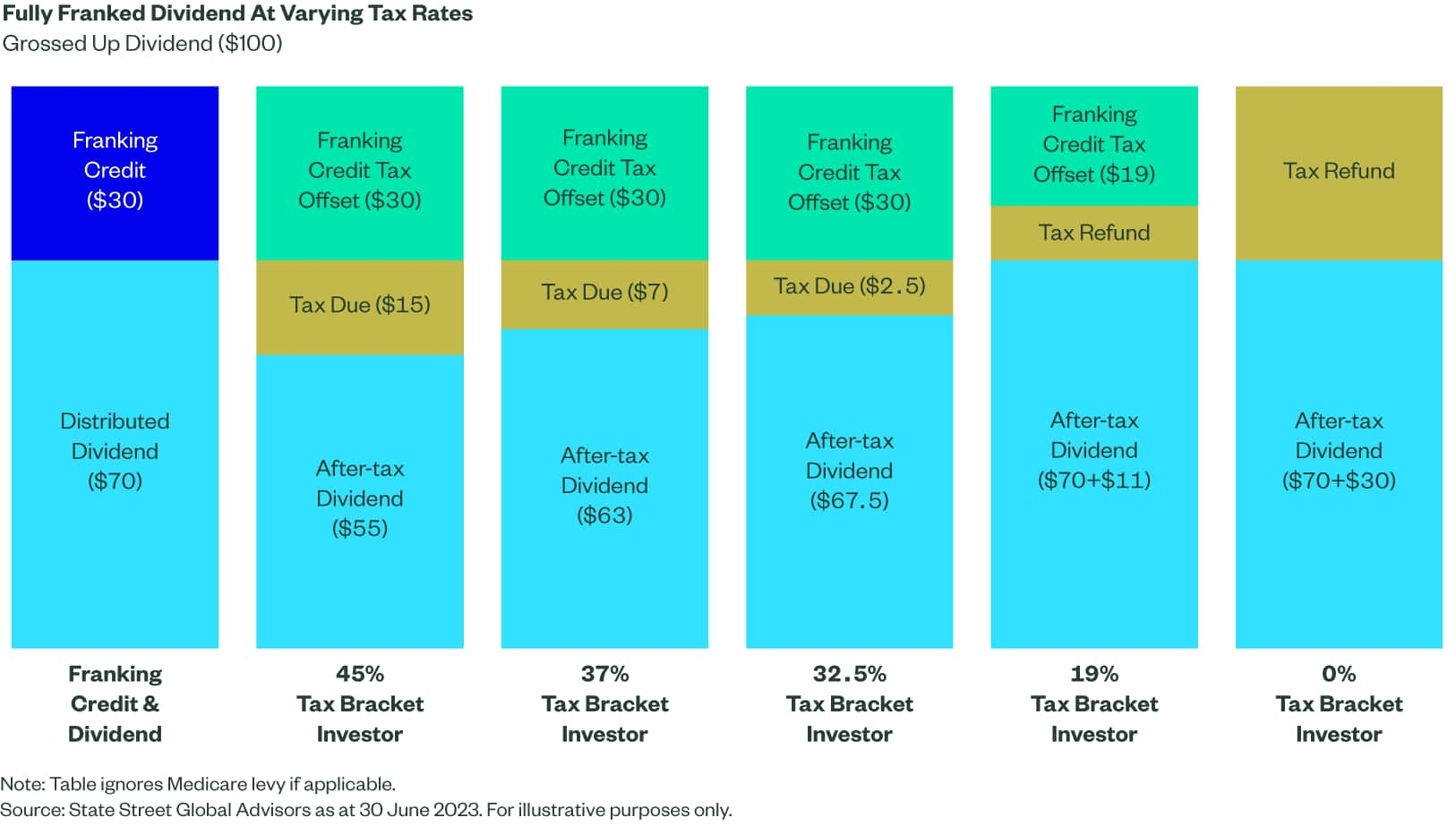

The taxpayer must pay tax on the full grossed-up dividend, but this tax will be reduced by any franking credit. In other words, the franking credit can be used to offset taxes due on the dividend (for 45%, 37% and 32.5% marginal tax rate investor) or entitle the investor to a tax refund (19% and 0% marginal tax rate investor). An investor with 0% taxes due will be entitled to receive the entire franking credit back as a tax refund. (Figure 1 below shows the example involving 100 shares of ABC Corporation).

Dividends and Franking Credits for the Australian Investor

A company that pays all its income tax domestically in Australia will usually pay a fully franked dividend, i.e. a dividend with a franking proportion of 100%. However, some companies’ franking proportions can be less than 100%, especially for companies paying taxes outside of Australia.

Other companies that do not pay any Australian tax, and have no franking credits from prior years available to roll forward, may pay an unfranked dividend. The franked vs unfranked proportion of a stock will therefore have a material effect on after-tax returns making it an important issue for all investors to consider.

ETF Investors Can Receive Franking Credits

Equity-based ETFs hold a basket of stocks that pay varying levels of dividends, at varying levels of franking proportions. Investors holding Australian share ETFs on and around the distribution dates (which can be quarterly or semi-annually, for example, month end June and December) could receive valuable franking credits along with any cash distributions they receive.

Importantly, investors must hold a security for 45 days around a distribution or dividend date to be eligible for a franking credit. There are two important consequences for ETF investors of this “45-day rule”.

- ETFs often have low turnover, holding their investments for long periods of time. This minimises the risk that an ETF will lose franking credits by breaching the 45-day rule. An ETF can then pass these franking credits to its investors at the next distribution date.

- Investors who own ETFs should take care when buying or selling on the stock exchange close to the ETF’s distribution date. Investors should check with their tax advisor before selling close to a distribution date to ensure they can make the most of any franking credits the ETF distributes.