Eurozone sovereigns: Selective immunity from the post-pandemic fiscal strain

As eurozone sovereigns’ spreads compress and risk rankings shift, understand how and why investment strategies are evolving across Europe in 2025.

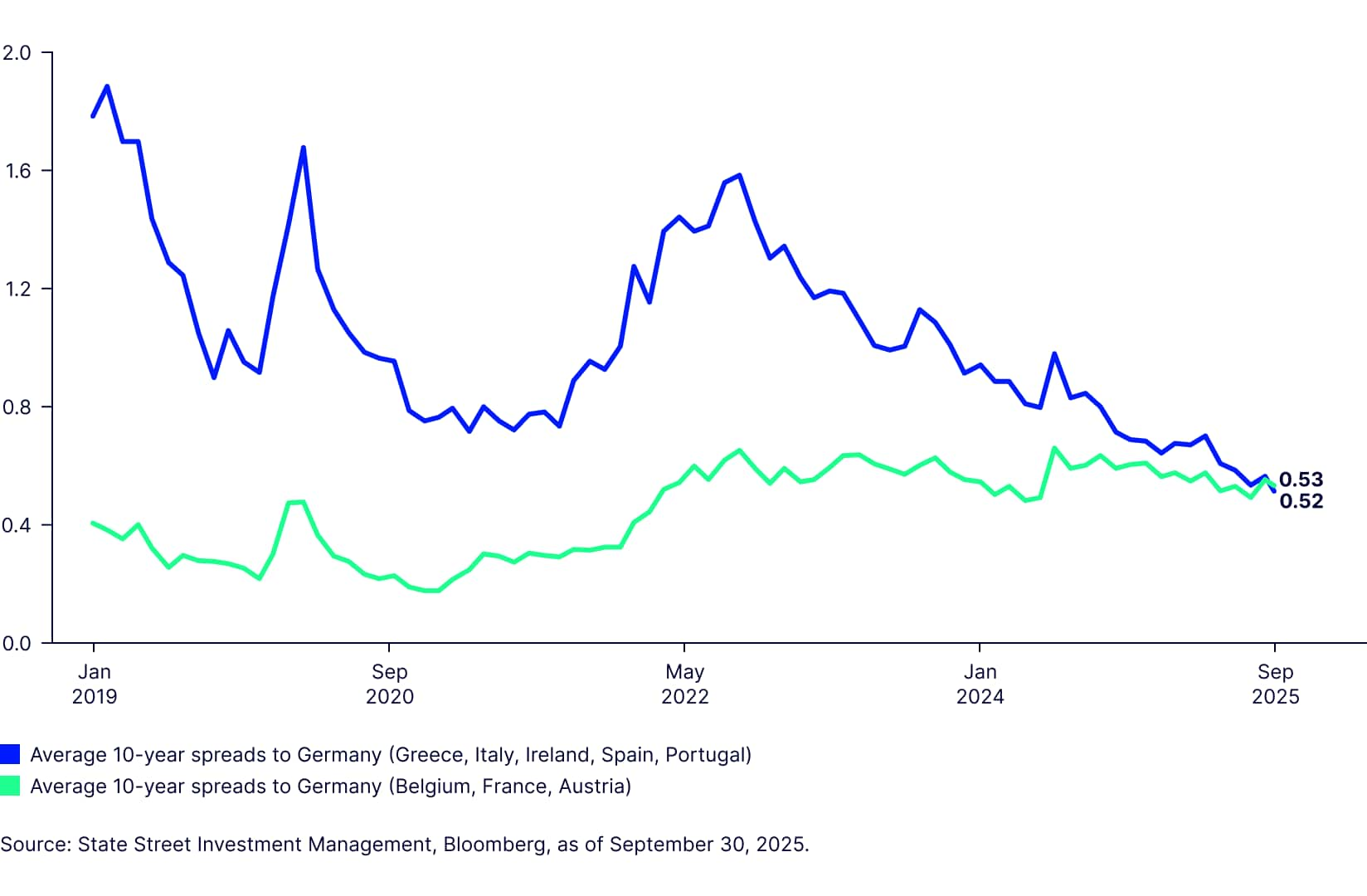

European sovereign bond markets continue to undergo a profound transformation. Investors have witnessed a compression in spreads, to levels not seen since before the global financial crisis (GFC) in many cases. At the same time, an extensive re-ranking of sovereign risk has been taking place between each country.

Figure 1: Eurozone sovereign spreads: Converging yields, diverging fundamentals

On the surface, the current compression in spreads resembles the period between the euro’s introduction in 1999 and the GFC, when differentiation in sovereign risk was minimal. However, the convergence now appears more cosmetic than structural. The old adage about being nice to those you meet on your way up as you may also meet them on the way down feels increasingly relevant—particularly for the peripheral European countries (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain). Meanwhile, members of the semi-core group—France, Austria, Belgium, and Finland—have also seen their relative standing weaken as their fiscal and debt dynamics diverge and are re-rated across the eurozone.

Figure 2: Ranking of selective eurozone sovereign spreads to Germany

| End 2020 ranking | Current ranking | Change in ranking | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | 1 | 1 | - |

| Austria | 2 | 3 | -1 |

| Finland | 3 | 5 | -2 |

| Belgium | 4 | 8 | -4 |

| France | 5 | 11 | -6 |

| Ireland | 6 | 2 | +4 |

| Slovenia | 7 | 4 | +3 |

| Latvia | 8 | 7 | +1 |

| Portugal | 9 | 6 | +3 |

| Spain | 10 | 9 | +1 |

| Italy | 11 | 12 | -1 |

| Greece | 12 | 10 | +2 |

Source: State Street Investment Management, Bloomberg, as of September 30, 2025.

Various factors are driving both the general spread compression and re-ranking, including the following:

German fiscal expansion

The announcement of German fiscal stimulus, along with the anticipated increase in bund issuance, has driven up German yields, and in the process made bunds relatively less attractive to own from a fundamental and technical perspective, thereby compressing spreads versus other EGBs.

Improving fundamentals

Italy and Spain have seen notable improvements in their twin deficits and, in both cases, this has translated into credit upgrades. Ireland has experienced a boom in its tax revenues and growth from multinationals, while Greece and Portugal have avoided the fiscal slippage evident elsewhere.

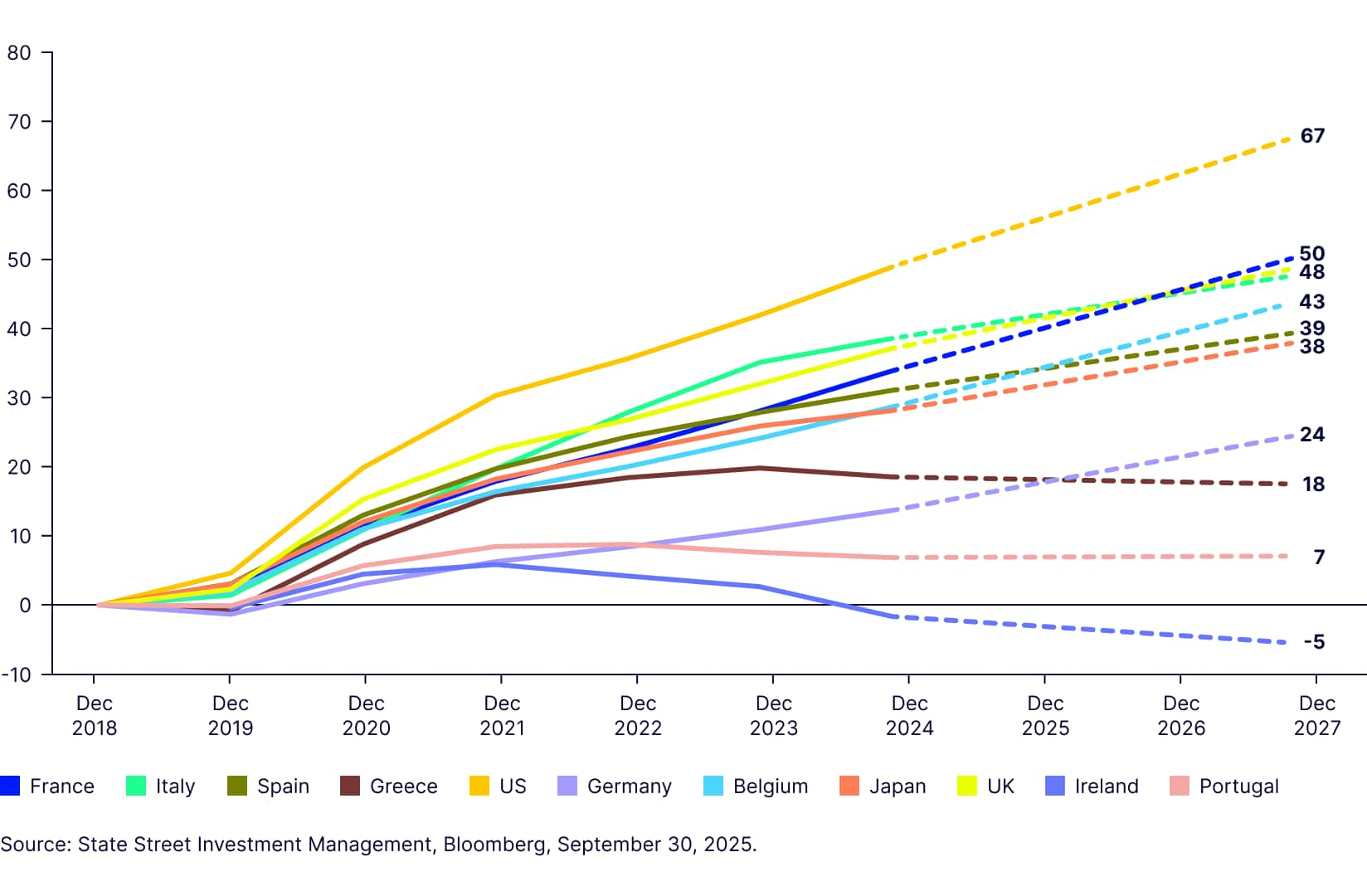

Figure 3: Higher debt levels are due in part to the post-pandemic fiscal backdrop

Cumulative budget deficits as a percentage of GDP, including expectations to 2027

Semi-core underperformance

The cocktail of an already high debt stock, outsized deficits relative to the economic backdrop, and a more price sensitive buyer in the absence of ECB purchases, has led to France, Austria, and Belgium moving down both the rankings and the ratings scales.

Debt sustainability: Cosmetic gains or structural progress?

Despite the similarity in spread levels across the eurozone, the outlook for both debt sustainability and long-term economic trends are very mixed. The market has rightly rewarded fiscal prudence but vulnerabilities still lurk in the wings.

The European Commission’s Debt Sustainability Monitor 2024 highlights the growing divergence in debt trajectories across the euro area and the differences are stark:

Debt trend

Most eurozone sovereigns can expect to see their debt levels continue to rise, especially since forecasts of future debt do not take into account the asymmetric impact of “shocks” on debt that have occurred with some regularity, with subsequent fiscal tightening usually being able to restore only a fraction of the shock induced loosening. Of the countries detailed in Figure 4, it is very interesting to note that only Ireland, Portugal, and Greece show falling debt levels on current expectations in a world of rising sovereign debt.

Medium-term risks

France, Austria, Belgium, and Finland feature as those with high medium-term risks alongside Spain and Italy. However, it is notable that Italy, despite its reputation and debt stock, has not seen a material deterioration in its market standing or fiscal outlook relative to its peers. In fact, Italy’s spread ranking has remained stable, and its fiscal deficit for 2024 was 3.4% of GDP against a final government projection of 3.8% and an original budget of 4.3%.

Figure 4: Euro area debt sustainability: Key country comparison (2023 baseline)

| Country | Debt level 2035 (EC) | Debt trend | Medium-term risk | Long-term risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 69.40% | Rising | Medium | Medium |

| France | 142.50% | Rising | High | Medium |

| Italy | 156.90% | Rising | High | Medium |

| Spain | 112.10% | Rising | High | Medium |

| Portugal | 74.50% | Falling | Medium | Low |

| Greece | 119.10% | Falling | Medium | Low |

| Belgium | 126.40% | Rising | High | High |

| Netherlands | 50.10% | Rising | Low | Medium |

| Ireland | 13.40% | Falling | Low | Medium |

| Finland | 96% | Rising | High | Medium |

| Austria | 98% | Rising | High | Medium |

Source: European Commission, Debt Sustainability Monitor 2024, March 17, 2025. Updated for Germany using May 19, 2025, update.

Long-term risks

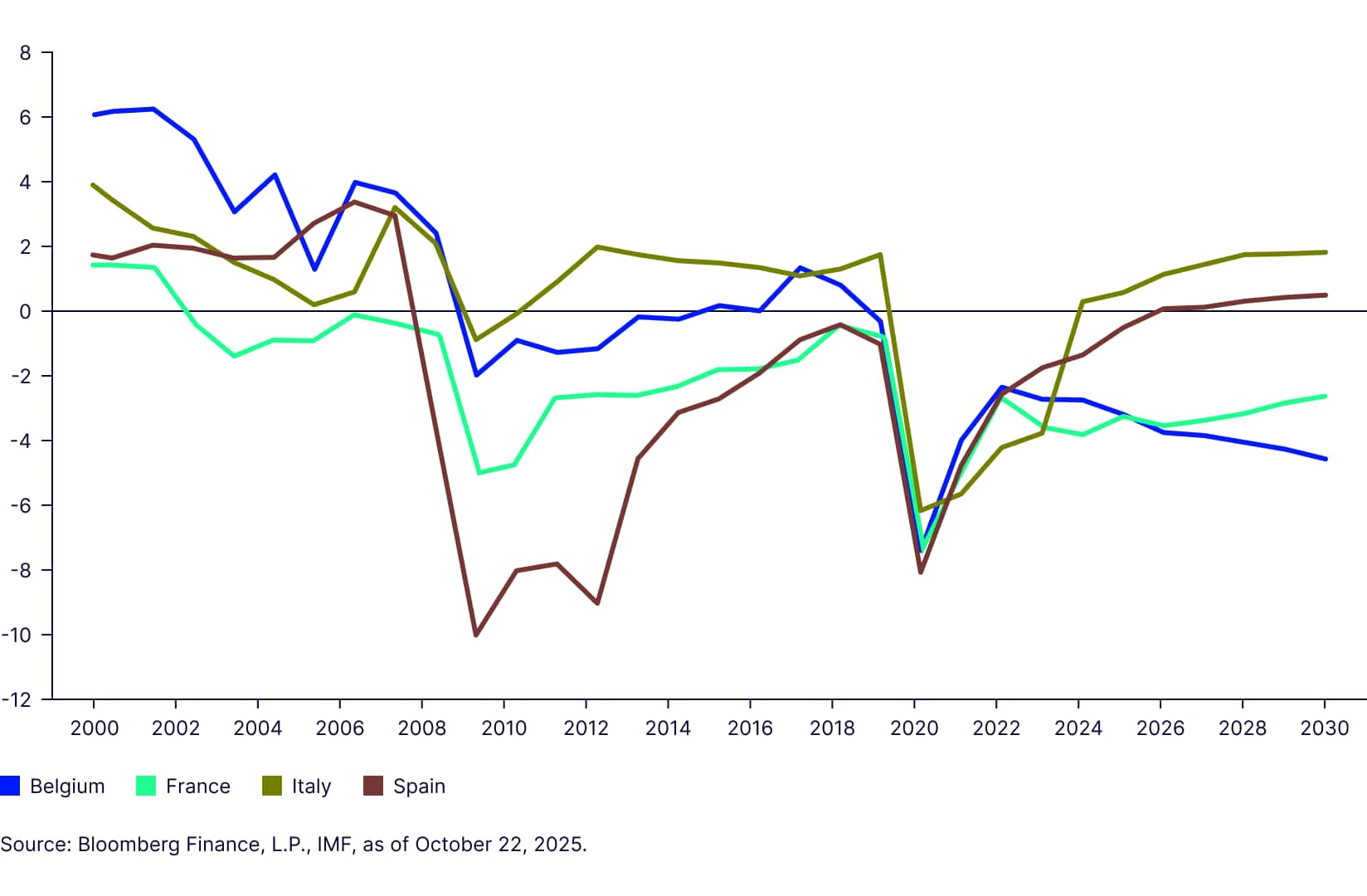

Belgium gets special mention within this group given the immense fiscal effort required to stabilize debt in the long term. It stands out as one of the more pronounced examples of the challenges many developed economies are likely to face. Belgium is projected to require a structural primary balance improvement of 6.7% of GDP in 2026 to place its debt trajectory on a sustainable long-term path. This adjustment is predominantly driven by aging-related expenditure pressures, contributing 3.7% of GDP—with pensions accounting for 2.3% and health care for 1.4% with the remainder due to the unfavorable budgetary position. France’s required adjustment of 3.4% to stabilize its debt almost seems reasonable in comparison. The political will from any corner to address these challenges is sadly absent.

Italy: From ‘bad boy’ to relative resilience

Among the largest eurozone sovereigns, Italy stands out as an exception. Once viewed as the “bad boy” of the bloc, Italy’s fiscal and market position has not deteriorated in the recent period—unlike France or Germany. Its spread ranking has barely changed, and while its debt trajectory remains a concern, Italy has not experienced the sharp re-rating or market punishment seen elsewhere.

Where does this leave investors?

The recent trends in European sovereign spreads highlight a number of takeaways for investors.

The entrenched mindset of core/semi-core/periphery, a once-helpful simplification has become increasingly redundant and even detrimental when thinking about the ranking and likely movement in eurozone sovereign bond yields in the future.

Credit ratings—and, by extension, portfolio allocations and index compositions—tend to follow market repricing with a lag. This delayed reaction function can create opportunities for proactive portfolio management, particularly when the underlying market drivers are more structural rather than cyclical in nature. In such cases, a proactive approach to portfolio composition and index choices, anticipating rating or index changes ahead of formal revisions, can be advantageous. For example, in countries such as France and, more recently, Belgium, a combination of generous welfare systems, indexed wages and benefits, narrow tax bases, and sluggish productivity growth persists alongside persistent political gridlock. Many of these elements are slow-moving and deeply embedded in the economic and political architecture, making them more predictive of long-term ratings trends. As such, aligning portfolio composition or index selection with these enduring realities can help enhance strategic positioning.

Figure 5: France runs a structural deficit not linked to shocks: IMF forecasts for 2025 and beyond

Government net lending/borrowing ex-interest expense as a percentage of GDP

While markets have rewarded peripheral countries for their recent fiscal prudence, their vulnerabilities have not gone away. Italy and Greece remain structurally hampered by high debt stocks. Ireland’s debt level is expected to fall to minimal levels, as it was before its banking and real estate crisis and subsequent IMF bailout, a reminder of how quickly things can unravel given its openness and concentrated revenue sources. The Spanish and Portuguese current fiscal approach is commendable but at the mercy of the prevailing political currents.

While the incentives for fiscal prudence have increased in line with investors’ heightened fiscal sensitivity, the demands on many governments will also likely grow—either through current bloated welfare programs, or new demands regarding defense, climate investment, and adverse shocks. In the absence of central banks’ protective quantitative easing cloak, this tension reveals itself in episodic revolts by the bond market that will likely become the norm given these structural vulnerabilities.

The re-ranking within the eurozone sovereign market is a microcosm of this general environment, and an agile approach unanchored from categorization will benefit from the continued re-ordering between them. Despite a general trend of spread compression, investors and policymakers must remain attentive to country-specific risks—the projected differences in underlying fundamentals, vulnerabilities and debt sustainability metrics are too large for the current convergence of yields to become the norm.